The Arrival

Thirty years ago this week, an 18 year old walked up to the front door of McDonough Gymnasium and went inside prior to the onset of the playoff round of the 1994 Kenner summer league. In an era before the Internet, before cell phones, and certainly before social media, he arrived virtually unknown.

In his book, "Not a Game", author Kent Babb recalls Georgetown forward Jerome Williams approaching what appeared to be a high schooler in the stands and asked if he had seen this newly signed guard from Hampton, Virginia.

"You mean me? he responded.

A few minutes later, with a jersey handed to him by league organizer Eddie Saah, the young man took the court. With an opening three pointer, Saah announced the name to the 700 in attendance:

"Allen Iverson".

A buzz enveloped the crowd. He would never be this unknown on a basketball court again.

The real story of that weekend was not who he was, but how he got there in the first place, a story of a young man, a coach that said yes, and a young attorney who brought the two together.

More than eight decades earlier, Georgetown welcomed a quarterback from Meriden, CT named Harry Costello, who became one of the nation's top players of the early 1910s despite standing just five foot seven and weighing under 140 pounds. It was Glenn (Pop) Warner that paid Costello a lifetime compliment when he proclaimed that "for his inches, one of the finest players who ever lived."

The same plaudit could have been directed at Iverson, who despite his size was an attraction before he even arrived in high school.

|

"When Iverson was a five-foot-six, 145-pound eighth grader, hundreds of fans would come out to watch him play for Bethel's junior varsity team," wrote Tim Casey in a 2016 article. " The next year, he started at wide receiver and safety on the varsity. In his sophomore season...Iverson tied a Virginia record by intercepting five passes in one game and helped Bethel to an undefeated regular season before losing in the first round of the playoffs." As a junior, Iverson led Bethel to is first state championship in 17 years. Trailing 16-0 in the fourth quarter of the semifinal vs. Richmond Huguenot, Iverson scored 22 consecutive points in the Bruins' 22-16 comeback win. A week later, he threw for 201 yards, collected two interceptions, and returned a punt 60 yards for a touchdown in a 27-0 win over Lynchburg's E. C. Glass HS. Glass coach Bo Henson, who later coached against Tidewater high school standouts Ronald Curry and Michael Vick, later said neither compared to Iverson. Soon, Notre Dame and Florida State were at the top of Iverson's recruiting list. "Football is always going to be my No. 1 sport," Iverson told CBS Sports in 2015. "It was my first love. Obviously if things went another way, I probably would have ended up playing football instead of basketball, but God got his way of doing things." For however amazing Allen Iverson was on the gridiron, he was just as spectacular on the court. Three months after being named Virginia's football player of the year, he repeated it in basketball, averaging 31 points a game en route to the state title. As a junior, he set the state scoring record at 982 points for the season, a record that lasted for 25 years until Mac McClung topped it in 2018. |

|

Known colloquially as "Bubbachuck", Allen Iverson was a folk hero in the seven cities of the Hampton Roads region: Norfolk, Portsmouth, Newport News, Chesapeake, Hampton, Virginia Beach, and Suffolk, and certainly the most prominent basketball prospect from the region since Chesapeake's Alonzo Mourning. The fame and adulation surrounding Iverson won him lots of friends. It made some enemies, too.

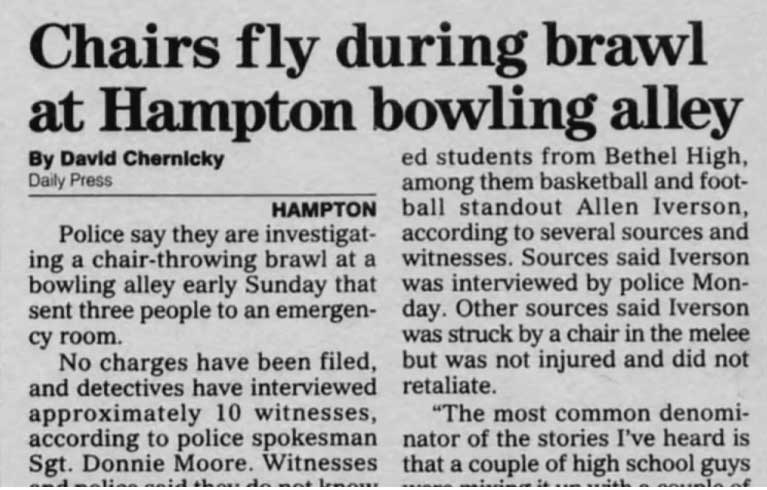

On the evening of February 14, 1993, Iverson and five friends arrived at the Circle Lanes Bowling Alley, located five minutes east of Bethel High School. At the snack bar was a group of eight bowlers drinking beer from the nearby town of Poquoson, seven miles north. In stark contrast to the minority populations of the region, Poquoson was anything but-- with just 84 black residents among a total population of 10,728, according to the 1990 Virginia census, it had the fewest black residents of any independent city in the state. All eight in the Poquoson group that evening were white.

|

What exactly happened next was, and remains, unclear. A 22 year old Poquoson man, Stephen Forrest, claimed Iverson walked over to the group and started cursing at them, when he saw "approximately twenty-five males coming from the other end of the bowling area." He said that some of them were throwing punches and throwing chairs at him, and he returned chairs in response, but testified that Iverson did not hit him nor did he see Iverson engage in the fight. A Poquoson woman with Forrest told authorities that chairs were being thrown by both groups, including by her, whereupon she was hit, but did not identify Iverson as an assailant. A third Poquoson woman said she saw Iverson standing by the fracas, but not thereafter, and was not throwing any chairs. Iverson said that he was called a "ni##er" by a man at the snack bar, who subsequently swung a chair at him, hitting him, whereupon other black students headed to the scene and the brawl ensued. Iverson said he was taken away from the disturbance by friends, and others also reported Iverson had already left the building as the fight ensued. |

|

The charge was perhaps as shocking as the arrest itself. What could have been filed as a fight among teenagers, or with misdemeanor assault charges, was passed over by Hampton prosecutors in lieu of the charge of "maiming by mob", a class 3 felony in Virginia. The charge, enacted after the Civil War to protect newly freed African Americans from white reprisals, was turned on its head.

A charge of misdemeanor assault would have likely resulted in a fine or probation for Iverson, whose only other brush with the law was a citation for driving without a license in 1992. A felony charge might result in prison.

"He'd taken the local high school to state football and basketball championships one after the other and seeing that [charge] was a travesty," said Butch Harper, who ran youth leagues in the city. "Blacks felt that if a white boy had done those things [athletically], he'd have been riding the shoulders of the community, not going to its jail."

In place of a jury trial, a bench trial (trial by judge) was ordered. If Iverson's supporters hoped that a judge would push back on the claim of maiming by mob, they could have not have found a less sympathetic jurist than the assignment of 65 year old Nelson Overton to the case, a man who all but threw the book at Iverson and the co-defendants. Described in his 2005 obituary as a "Southern gentleman" and "an unreconstructed old fashioned lawyer and judge," Overton was a mercurial sort who, in his family's words, "obeyed the letter of the law and the compass of his own mind."

The trial moved swiftly over two days. Stories differed across multiple witnesses. A defense request to present a video of the incident, one which did not show Iverson in the fracas, was denied by the judge. Smith's testimony, despite changes in his story between the initial investigation and at trial, was accepted by the judge without prejudice.

Prosecutors urged Overton to make an example of Iverson and the three men. Referencing Iverson's appearance at a Nike basketball tournament event the weekend before the trial, the Commonwealth's Attorney told the judge, "Now it's our turn to just do it."

If there was reasonable doubt raised at the conflicting testimony, the legal definition in Virginia of maiming by mob, where any member of a mob was guilty of the offense of the mob as a whole, offered Overton little wiggle room, and he chose not to explore it. Overton found all four men guilty, and two months later sentenced Iverson to a stunning 15 years in prison, suspending ten of the 15. He denied Iverson bail and sent him directly to confinement that morning.

"Mr. Iverson had two choices - either stay and participate, or get out," Overton said. "He stayed and participated, and became a member of the mob. He made the wrong choice."

The sentencing ignited and divided the communities surrounding Hampton.

"This thing was blown way out of proportion," said Boo Williams, Iverson's former summer league coach. "The judge feels the pressure from the other side and is just trying to make an example of Allen Iverson."

"People tell me that the only other time when things were more tense racially here was after the King assassination," said Hampton Roads Daily Press columnist David Teel.

In a 2010 interview for his ESPN feature "No Crossover: The Trial of Allen Iverson", documentary film director Steve James, himself a native of Hampton, spoke about what the conviction meant to the larger community.

"It largely divided along lines of race, where the black community felt like they had to protect this kid and his future, and the white community felt like 'this kid's not gonna get away with this'", he said. "I think it definitely opened up and tapped into all this underlying resentment and racism and feelings of division between the races and made it very public."

Allen Iverson began his sentence in September, 1993.

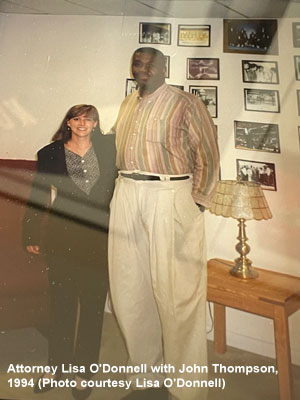

The family rotated through a number of attorneys before reaching out to Thomas Shuttleworth, a Virginia Beach attorney who took the case pro bono. Shuttleworth approached one of his firm's associates, presented her a storage box full of files, and assigned her the case of a lifetime.

The appeal of Allen Iverson was underway.

When the story of Allen Iverson's arrival at Georgetown University is told, the name of Lisa O'Donnell is rarely cited. A native of Leesburg, VA who graduated with a J.D. from George Mason University in 1990, O'Donnell moved to Newport News to begin her career as an attorney with the firm of Shuttleworth, Ruloff, Giordano & Kahle. The more she began to study the case, the more it steeled her resolve.

"This was an injustice," she said. "I had to do something about it."

The law firm was looking for ways to reduce the sentence through the appellate process, but it would not be easy. Protests in the community were still common in the Hampton Roads area, and any attempts to have Overton's bench verdict overturned would face long and considerable pushback in the court system. Meanwhile, a story in Sports Illustrated that fall caused further heated reactions in the community and led to a libel suit from an employee at Circle Lanes. The magazine later went to the unusual step of a full page apology, stating that "portions of the story were not up to SI's standards."

For Iverson, now confined at the minimum security City Farm in Newport News, his future after confinement was dimming. Following his sentence, Iverson still needed to complete his high school requirements before he could even pursue college; however, the schools that had so heavily recruited him had all but disappeared.

Following an introductory meeting with Allen's mother, Ann Iverson, O'Donnell visited Allen Iverson for the first time at City Farm. Two important issues came out of the visit that set the course for the legal challenges to follow.

|

O'Donnell asked him what he wanted to do after he was released. Allen said that he would now focus on basketball, not football. When O'Donnell asked where he wanted to go to play basketball, Iverson told her he wanted to play at Georgetown University. Georgetown had not recruited Iverson to this point, but when O'Donnell reconnected with Ann Iverson, she was excited at the prospect of her son playing under the legendary John Thompson. But was Georgetown interested? "We had to meet [Coach Thompson]." O'Donnell recalled. "I made a cold call to him." Thompson picked up the call and agreed to the meeting. The two drove from Hampton to Washington. "Isn't he [still] in jail?" Thompson asked. "I'm getting him out," O'Donnell said, but told Thompson it could be as much as two years to get through the legal process. Thompson pushed back, saying that in two years, Iverson would lose much of his skills and by that point would not be an asset to his program. O'Donnell said Ann Iverson began to cry. "They're going to kill him [there]," she pleaded. "But I had a card up my sleeve," O'Donnell recalled, and that was to approach Virginia Governor Douglas Wilder to consider a pardon. The possibility of Iverson moving on to a program like Georgetown might be enough to secure interest from the governor, who was term-limited and scheduled to depart the office in early January. Time was of the essence, as governor-elect George Allen might not be inclined to take on the case so early in his term. |

|

"I'd like to see your brief," Wilder said.

One December 29, 1993, two weeks before the end of his term, Wilder issued a conditional clemency order for Iverson, effective Dec. 31.

"The Governor found that while there was not sufficient evidence to grant the extraordinary relief inherent in a traditional pardon, there was sufficient doubt to merit that Allen Iverson be granted limited freedom and the opportunity to continue his education," read an official announcement.

Among the stipulations, Iverson must complete high school, observe a nightly curfew, and not engage in any competitive sports until a parole date, then set for August 23, 1994.

"The governor granted Allen Iverson conditional clemency. Why? Because Iverson and his counsel asked for it,." wrote the Daily Press. "According to Wilder, they cited such things as "reasonable doubt as to his guilt, the fact he has no prior criminal record and his desire to be allowed to continue his education."

"Allen wrote the governor explaining that he wanted an opportunity to get his education so that he could make a valuable contribution to society," said Gary Moore, a former youth league coach of Iverson, to the Washington Post. "His letter didn't ask for specifics, it just asked for a chance at life."

Wilder's decision, including clemency orders effective two weeks later for the other defendants, was controversial, but was incumbent on the three young men meeting its terms, which they did.

O'Donnell's work wasn't done, as she and the firm turned its collective attention to the Virginia Court of Appeals. For Iverson, the work was just starting. Returning home, he began a seven month effort to complete s high school diploma through Richard Milburn High School, a state-supported program for at-risk students. The family engaged with Sue Lambiotte, a private tutor whose son had actually played with Iverson as a 13 year old, to improve his math skills. And if all this wasn't enough, Iverson still needed to take the Scholastic Aptitude Test and to improve on a 1.7 grade point average from Bethel to the NCAA minimum of 2.0.

If he could meet these challenges, and abide by the terms of the clemency, Iverson would have a scholarship from Georgetown University.

On April 19, Allen Iverson was offered and signed a letter of intent to attend Georgetown, through, in typical Georgetown fashion, it was not announced for six weeks thereafter. Though Shuttleworth indicated to the press that Iverson would not complete his diploma requirements until late July or August, John Thompson was confident.

"If I had not seen some commitment, some willingness to succeed, I never would have gotten involved," Thompson told the Washington Post. "There's nothing at all wrong with Allen's ability to read or write. That's what I found very encouraging. He's an extremely bright young man. He just needs the discipline and direction to succeed."

"I am happy that Coach Thompson and Georgetown have taken this interest in me," Iverson said in a Georgetown release. "I will do my best to take advantage of this chance to continue my education."

Like much in the John Thompson era, the arrival of Allen Iverson to the Kenner League was no accident. While he had signed a scholarship offer with Georgetown, the program was technically over the 13 man scholarship limit of the NCAA, even with a transfer two weeks earlier from center Duane Spencer. On the day Iverson arrived in August, the basketball office quietly announced the departure of a second sophomore, Eric Micoud, to perform military obligations in France. This gave Georgetown an opportunity not to pass over questions of a lack of scholarships, despite a wisecrack from Washington Post columnist Tony Kornheiser that suggested Thompson had now sent a player to the French Foreign Legion.

That Iverson played at all that weekend in August was also a function of good timing. Upon the terms of the clemency agreement, Iverson was not allowed to play competitively until his parole date of August 23, but when the date was moved up to July 26, he secured the approval of his parole officer to leave the state and cross the Potomac a week later.

Iverson's debut was nothing short of historic for the Kenner League, which had been in action since 1982. He stunned the Thursday night crowd of 700 with 30 points by halftime and 40 overall in a 75-67 win by Georgetown's summer team, named for and sponsored by The Tombs.

The next evening, following a brief game recap in Friday's Washington Post, a crowd of 2,000 filled the gymnasium for the semifinal, where he scored 33 in a 106-90 semifinal win. "The standing room only crowd was treated to a breathtaking offensive display," wrote the Washington Post the next day. "Iverson made 12 of 16 attempts and didn't miss until the 3:56 mark in the first half."

"His final points of the first half came via an inbounds alley-oop pass that was the highlight of the evening. He sneaked in from behind the three point line, began his leap from just inside the free-throw line and grasped the ball high above the rim before punctuating the play with a backboard shaking dunk."

In a moment of either serendipity or skulduggery, a unnamed fan that evening had smuggled a video recorder into the game, which was strictly prohibited by Kenner and Georgetown officials. Posted to YouTube many years later, a two minute excerpt is a rare look at Iverson's first moments on the Hilltop:

By the time of Sunday's final, campus security was called in to prevent fans from further exceeding capacity, which swelled to its pre-1982 number of 4,000. Hampered by a sore ankle, Iverson scored 26 in the Tombs 72-66 win.

"Physically, Iverson is the most gifted player I've ever seen," said basketball recruiting analyst Tom Konchalski, who drove down from New Jersey just to see Iverson play. "He's much more explosive than [1994 NBA All-Star] Kenny Anderson, and he's a better leaper."

And as quickly as he arrived on Thursday, he was back home by Sunday evening. Iverson's weekend at the Kenner League was a respite against a whirlwind of academic requirements still to be met. His SAT scores cleared in late summer, and he completed his final credit hour at Milburn only on September 3, allowing him to graduate and register at the University with two days to spare in the late registration period. His first formal practice with the team was a month later, with a pair of exhibition games in November that only elevated his aura entering the 1994-95 season.

Added to the Georgetown lineup two minutes into its November 8 exhibition game with Ft. Hood, TX, Iverson scored 24 points over the next eight minutes, 28 by halftime and 36 overall. Two weeks later, he scored 39 against seven members of the Croatian national team.

"I saw Lew Alcindor, Austin Carr, Moses Malone, Alonzo Mourning, Albert King, Ralph Sampson and Patrick Ewing play in high school. I saw Adrian Dantley in the eighth grade," wrote veteran Washington Post columnist Thomas Boswell. "But I know what Iverson was last night at McDonough Gym - the most exciting unproven teenager I've seen since Alcindor."

Iverson's college opener was a little more down to earth, as Thompson introduced his freshman guard to the defending NCAA champions, #1-ranked Arkansas. Iverson shot just 5 for 18 in a 97-79 loss, but began a season of maturation for a player that had not played competitive basketball in over a year.

|

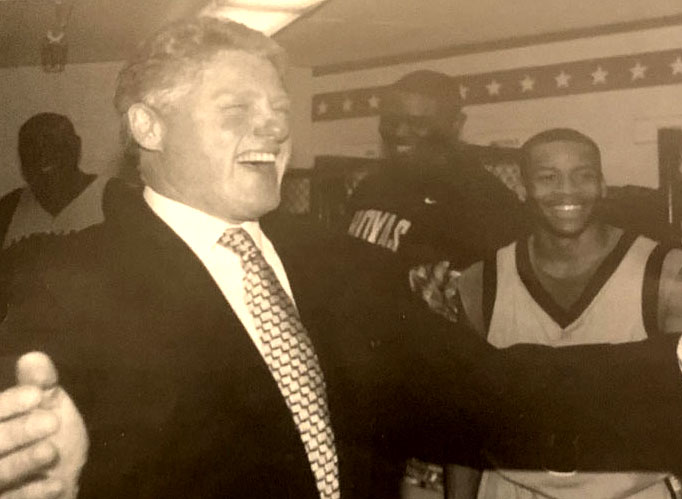

As the season unfurled, Iverson had his high points (back to back 30+ point games in December versus DePaul and Providence), and low points, including a foot injury which limited him to ten minutes and a career low two points versus Villanova at the Spectrum. The game was overshadowed by poor sportsmanship from Villanova students, where a large sign was unfurled which read: "Iverson: The Next O.J". Iverson reserved comment but let his game do the talking, averaging 22.2 points over a four game run in Big East play, When Villanova arrived to US Air Arena three weeks later, Iverson put on a show for the 17,969 in attendance, including President Bill Clinton, with 26 points, seven rebounds, seven assists, and five steals in a 77-52 rout of the #9-ranked Wildcats. Clinton visited the Georgetown locker room after the game to congratulate Iverson and the team, and in a brief moment the young freshman must have wondered how much his life had changed in just the past year. |

|

Even in good times, Iverson's legal issues were never far away. Three days after the Villanova win, Iverson got a call from Shuttleworth, who informed him that a $100 million malpractice suit had been filed by a Newport News attorney acting in Iverson's name, claiming that a prior attorney erred in not pursuing a jury trial. Iverson didn't authorize it and wanted nothing to do with it, and Shuttleworth had it thrown out of court.

"Quite frankly, I think the story is that there is a guy going out there filing suits for people he doesn't even represent," Shuttleworth told the Daily Press.

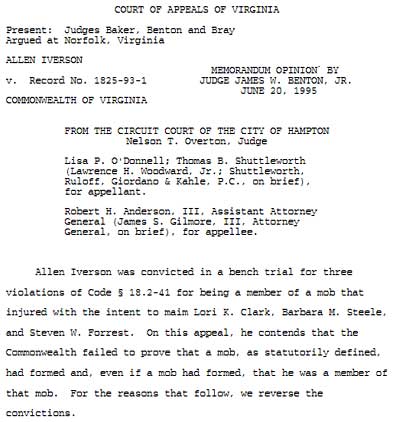

Two days after a road trip to Syracuse where the Hoyas upset the #17-ranked Orangemen 81-78, Iverson was back in court, as his legal team began its next move: having the sentence overturned.

While issues remained unresolved on questionable testimony, particularly from the employee at the bowling alley that identified Iverson at the scene, the appeal argued that insufficient evidence existed on the charge itself: maiming by mob. While defendant appeals through the appellate courts are often long shots, the Iverson case and its subsequent national coverage cast a critical light on the maiming by mob statute.

While the appellate court was at work, Iverson returned to basketball. At season's end, he was named the Big East Rookie of the Year and its Defensive Player of the Year, scoring 58 points in two conference tournament games before the Hoyas fell to top seeded Connecticut, 88-81, in the semifinal.

The first Georgetown freshman to average 20 points or more in a season, Iverson's numbers were held under average in two NCAA tournament games, but when Don Reid rescued Iverson's buzzer beating attempt and tipped it in versus Weber State, the Hoyas advanced to its first round of 16 game in six years versus North Carolina. UNC prevailed, 74-64, but Iverson scored 21 points of his 24 points in a 14 minute second half stretch that tested the Final Four-bound Tar Heels.

"Iverson's just a remarkable athlete who's going to be a remarkable college player," North Carolina coach Dean Smith said in post-game comments.

In his own post-game thoughts, Iverson was reserved but thankful.

"Next year, I'll have a way better season. I have to be more patient, hold down the turnovers, and get my teammates involved," he told the Washington Post "Next year, I can come in and just play my game."

As for all that preceded him, he replied, "I'm so glad that's over."

|

On June 20, 1995, the Virginia Court of Appeals issued its opinion. "Allen Iverson was convicted in a bench trial for three violations of Code Sec. 18.2-41 for being a member of a mob that injured with the intent to maim," the court wrote. "On this appeal, he contends that the Commonwealth failed to prove that a mob, as statutorily defined, had formed and, even if a mob had formed, that he was a member of that mob. For the reasons that follow, we reverse the convictions." In an excerpt of the decision, the appellate court noted that "reviewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the Commonwealth, the testimony proved that someone other than Iverson hit Forrest as Forrest and Iverson exchanged words. Iverson's confrontation with Forrest was an incident that may have precipitated a brawl but was separate from any mob activity. No evidence proved that Iverson was a member of any mob that later formed." "Although the evidence would have been sufficient to prove individual assaulted conduct, it was insufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Iverson acted as part of a mob. Therefore, the convictions are reversed and the case is remanded to the circuit court for such further action as the Commonwealth may be advised." Even in this pre-Internet era, word of the decision traveled fast, and was noted on sports pages nationwide. |

|

Upon learning of the decision, Thompson immediately phoned Georgetown president Leo O'Donovan S.J. "More than anybody else, he took an awful lot on his shoulders to give this young man an opportunity," Thompson told the Post. "When the president of an university does what he did, I couldn't call him fast enough to thank him."

In a statement, O'Donovan remarked that "Allen has worked very hard here at Georgetown. I'm convinced that this further justifies the confidence we placed in him."

In her comments to the Washington Post, O'Donnell added that "I would hope that the attorney general's office and Commonwealth Attorney's office would consider the fact that Allen has already spent several months in jail and consider some of the evidence that has come to light since the time of the trial and decide that it wouldn't be in anyone's best interest to pursue this matter any further."

On July 5, the Attorney General's office indicated it would not pursue a retrial. Three weeks later on July 26, the Commonwealth's Attorney concurred.

"To what extent Iverson was at fault will never be fully resolved to everyone's satisfaction," wrote an editorial in the Daily Press. "But there's no question he paid a price: four months of incarceration, reams of bad publicity, a disrupted education, an interruption in pursuing what is widely viewed as an extraordinary athletic career.

It continued:

"To Iverson's credit he has rebounded - and scored. He completed his secondary education without the familiar environment of Bethel High School and by all accounts has been a model student at Georgetown University. He has resumed the pace of an athletic superstar as if there been no disruption.Eleven months to the day after the decision to close the case, Allen Iverson was selected as the first pick in the 1996 NBA draft.

"[The] decision to let the case rest, on the heels of a similar disposition by the attorney general, should close the book on Iverson's legal difficulties. Let us all hope that the next time Allen Iverson needs a lawyer, it will be for the purpose of negotiating a multi million-dollar professional basketball contract."

Decades later, the story of Allen Iverson and his trial still is felt in the Hampton community, amidst the underlying issues of class and race that have been recognized but never truly resolved.

"I think I think it certainly exposed what was underneath the surface," Steve James said in the aforementioned interview. "Has it changed my hometown?... I'm not sure I know the answer to that because people feel just as strongly today about it as they did then."

The case was an important milestone for O'Donnell, who later served as President of the Virginia State Trial Lawyers Association and a fellowship with the National College of Trial Advocacy during her legal career. Particularly as a Virginian, she noted, the case strengthened her belief in pursuing civil rights for all her clients.

Allen Iverson's time at Georgetown was less than two years of his life, and he has rarely returned since--his last public appearance on the Hilltop was in 2014. Iverson retired from the NBA in 2013 and returned to the region where he grew up.

"This is my home. This is who I am," he said in 2019. "It's just a beautiful feeling seeing people that are here that actually care."

On May 5, 2024, Gov. Glenn Youngkin appeared in Newport News to proclaim Allen Iverson Day in the Commonwealth of Virginia and to rename a portion of 16th St. in his honor.

Amidst a number of comments by local officials, Iverson stepped forward.

"I'm so blessed to have the people, you know, my family and my friends around me that support me through my ups and downs and encourage me to do better, just doing everything to help me live this dream life...It's hard, you know, waking up every day and you know, it's always an uproar everywhere I go, trying to go to the grocery store by myself and do the things that regular people do.

"But I do it the Allen Iverson way."