Lights Out

On April 2, 1943, following the school's first NCAA Final Four appearance, the Georgetown Hoyas left New York, heading home. There would be no parades, no crowds awaiting them at the campus gates. It was neither the time nor place for it.

"Here's probably the last individual paragraphs on Georgetown's cage club of 1942-43 that will appear in print," wrote columnist Jack Donahue in the April 7, 1943 issue of the HOYA. "From now on they will be doing a greater job; without the press notices and cheering mobs of Madison Square Garden. And no one will compliment them on their performance. No trophies, awards or watches to the winners either....Every Hoya expects to be with Uncle Sam, in one way or another, quite soon."

"In most cases, very, very soon."

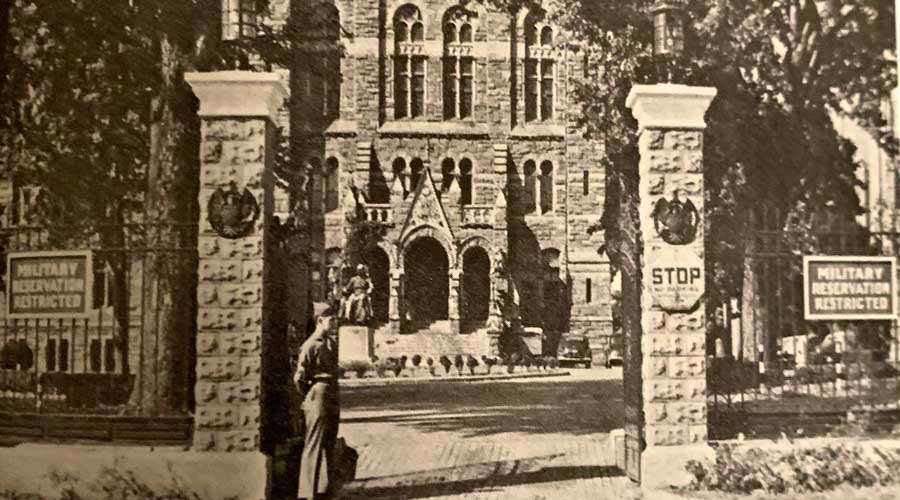

The Final Four was among the last gasps of traditional campus life in the spring of 1943. An abbreviated spring sports calendar limped into May, but not further. At this point, the University had become a military installation. Sports, at least as Georgetown had known it, would not return for more than two years.

Elmer Ripley's 1942-43 team, nicknamed the "Kiddie Korps" by local sports writers, was known for a cadre of New York area freshmen who rose to the top of the college basketball stratosphere in short order. It was no accident that Ripley played a team of freshmen and sophomores. In many cases, this was all the University had left as the United States entered a second year of war. The story of Georgetown in World War II gets passing notice in its long and storied history, but as was the case during the Civil War, the events of the day posed a threat to its very survival.

On September 6, 1940, eleven months into World War II and five months into the Battle of Britain, Congress passed the Burke-Wadsworth Act, also known as the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, the nation's first peacetime conscription act. With an uncertain entry date anticipated for the United States into the European theater, a standing army of just 174,000 men would be wholly insufficient for either insurgent or defensive needs. Signed by President Franklin Roosevelt ten days later, the bill instituted a lottery for all men between the ages of 21 and 36. For a college man of the day, this was concerning but not a direct threat to their undergraduate years, as deferments were in place for those enrolled in higher education. By the time the United States entered the War in December 1941, the draft age had been lowered to 20 and those 18 to 20 were obligated to register, but the deferment remained intact.

Millions of men had enthusiastically volunteered after Pearl Harbor, but the results (and the number of washouts) concerned the War Department. Of 20 million candidates, "fifty percent were rejected the very first year, either for health reasons or because 20 percent of those who registered were illiterate," wrote History.com. This would not be sufficient to fight a two front war Europe and the Pacific, and the potential of an invasion on either coast.

On November 13, 1942, President Roosevelt signed an amendment to the Act lowering the draft age to 18, and ending deferments in the spring of 1943. "The time has now come when the successful prosecution of the war requires that we call to the colors the men of eighteen and nineteen," he said. "Many have already volunteered. Others have been eagerly awaiting the call. All are ready and anxious to serve. The civilian careers of these men will be interrupted, as have the careers of most of their seniors. Large numbers about to enter the armed services will come from schools and colleges. The vocational and technical training which the armed services now offer to many will stand them in good stead."

The draft notices began by year's end. By January and February, students were leaving in regular numbers. Most of the varsity basketball team were receiving their draft notices that spring, one starter (Andy Kostecka) was called to duty three weeks before the end of the season. Aside from freshman Billy Hassett, designated 4-F (physically unfit for service) for a punctured eardrum, all were headed into the military. One of these men, Robert Duffey, left for the Army in June 1943, was awarded a BSS degree in absentia a year later, and died in the battle of Hurtgen Forest.

In 1942, the College graduated 198 men from a total of 713 enrolled. By 1943, just 58 seniors were awarded degrees that June. The School of Foreign Service saw its graduates decline in one year from 76 to 20.

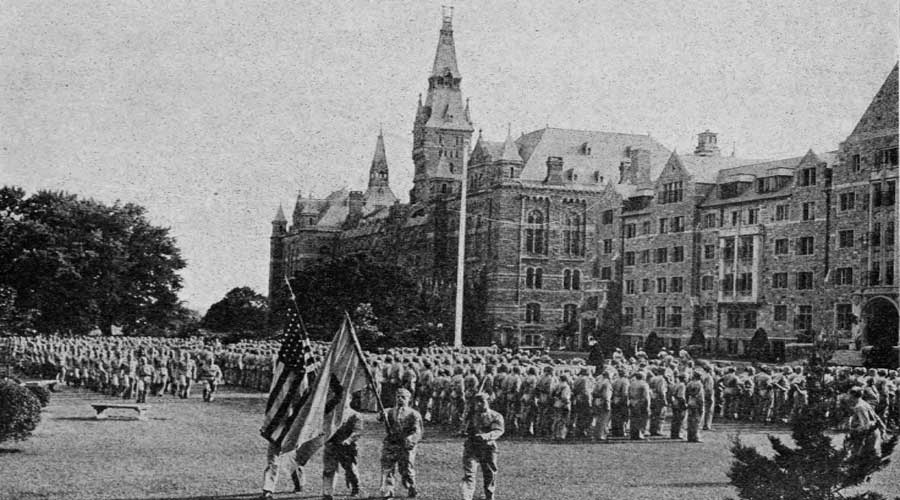

In late 1942, the War Department announced the formation of the U.S. Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), an accelerated program of skills for enlisted personnel before seeing combat, such as engineering. Designed primarily for land grant colleges, Georgetown was added to the list in the summer of 1943 for its foreign language training, and it helped keep the school open for the following year. At one point, as many as 1,800 servicemen cycled through Georgetown under the ASTP and a shorter series of accelerated courses known as the Specialized Training and Reclassification Program (STAR). Nearby, the medical and dental schools utilized the Navy's V-12 officer training program for students of its own. One major difference between the two was athletics: the ASTP soldiers were regular army, took classes only with other soldiers, and were restricted from athletic competition. The V-12 was a one year reserve officer training program which allowed intercollegiate competition, and V-12 programs at Notre Dame, Villanova, and the Big 10 provided athletes the opportunity for a full year of competition before enlistment.

Athletics at Georgetown, as least as was known prior to 1943, had ceased to exist. A handful of intramural sports existed for the remaining civilians as the servicemen had no such time to spend playing sports: theirs was a full day from reveille to lights out, physical training on the upper fields, parade marches on Copley Lawn, and training classes throughout the day.

(A notable alumnus of the ASTP program at Georgetown was a 21 year old Army interpreter named Carl Reiner (1922-2020), whose impersonations of Jesuits during a variety show at Gaston Hall not only brought down the house, but began a lifetime in comedy for him after the war. Reiner later became a television writer alongside another ASTP graduate who studied at VMI, Mel Brooks.)

The Ye Domesday Book recorded the transition for civilian students that year:

"We were being initiated into the mysteries of Minor Logic when, like a bolt from the blue, came the call to active duty for the members of the Army Enlisted Reserve Corps on February 9, the bulk of our class forming a large part of the 115 Georgetown Reservists affected by the order. Two weeks later, we lost several more juniors as the Army Air Corps Reservists were called to Miami Beach for flight instruction... The first contingent of soldiers arrived from camps in Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania on April 21st. We civilians soon grew accustomed to the fast tempo of military life, the bugle calls, the impressive retreats. Yes, Georgetown had opened her arms to many strangers in khaki, but strangers we soon called brothers, inasmuch as they and we were striving for the education which would fit us for the battle at the front or here at home... Final exams alone remained between us and vacation. We bade farewell to classmates and teachers, not knowing whether possibly it was our real farewell."

There appears to have been at least one attempt to restart an intercollegiate basketball program, however.

With nearly its entire coaching staff having headed to war, Georgetown brought in civilians beyond draft age to help provide the remaining students some semblance of physical fitness, for however long as they remained on campus. One of these was Vince McNally (1902-1997), who had played football and basketball at Notre Dame and had served as an assistant coach at Villanova before taking a part-time role with the Washington Redskins and a second job at Georgetown.

"Since coming to Georgetown, Vince has been an active member of the Physical Training staff," wrote The HOYA. "He has become a favorite among the soldiers as well as the students. Recently he volunteered to assume the coaching position to the Copley Kids and, considering the limited amount of time available for practice, he has done a splendid job. The students as well as the Athletic Department are anxious to see Vince McNally become a fixture here at the Hilltop. For that reason, combined with his extensive knowledge of sports and his coaching background, Vince is being groomed for a post-war coaching position at Georgetown."

Later that year, the HOYA reported an interesting story under the title PLANS FOR FORMING INFORMAL BASKETBALL TEAM MATERIALIZING . Citing "an official official announcement by the Christmas holidays", McNally would develop a schedule consisting of universities and some high schools, owing to the number of college programs suspended during wartime.

"Vince announced that he had more or less a tentative schedule in store and thinks that the Hoyas would fare well, even against some of the local college fives," it wrote.

The 1943-44 team was not to be: after the new year it was reported that the ASTP had received priority to use Ryan Gymnasium for physical training, and thus the opportunity for meaningful practice was infeasible. McNally left Georgetown two months later to become an assistant football coach at Holy Cross; three years later he began a 15 year career as general manager of the Philadelphia Eagles.

Even if practice time could have been arranged for a team, the dwindling student population could not support it. Fewer than 100 students remained in the College by the spring of 1944. The commencement program in June listed a total of just 21 graduates, with another 15 listed as "absent on duty with the Armed Forces". Basketball would have to wait.

More changes followed that summer. The War Department had grown impatient with the ASTP program and shuttered it; around the same time, the STAR program ended as well. With the servicemen gone, the campus was all but vacant by the fall. With every 18 year old man as draft eligible, the school relied on younger and younger students to fill its seats. Nearly half the total College enrollment by 1944, 90 of 182, were freshmen, and half of these were 16 or younger. Its youngest enrolled student was a 14 year old.

Another effort to revive basketball was announced in late 1944, but it too fell short.

"There are many plans now being formulated for a rebirth of Georgetown sports," wrote the HOYA on December 13, 1944. "A basketball team has been practicing for the past few weeks and hopes to arrange some games after the vacation. The call has gone out for a hockey team, and several have signified their desire to play. Boxing has gotten some attention this fall, and if there is interest next term, there will be a tournament next term." None took flight.

By the spring 1945 commencement, just four men were present to receive their degrees from the College, as 14 fellow graduates had already left for military service.

The end of the war in Europe brought renewed hope for a return to normalcy, and when enrollment surged to 335 in the College and 320 in the SFS that fall, athletics returned to the conversation. Basketball would return, but it would be a little more difficult.

Since the 1920s, Georgetown athletics was nominally led by a Jesuit moderator and a handful of men in the department of physical education, mostly football coaches. Most, if not all, were still on active duty. Elmer Ripley, the former basketball coach, was too old for the draft and had taken a coaching position at Columbia in 1943, where its V-12 program allowed it to field competitive teams. Ripley would have likely come back to Georgetown by 1945, but the school had been slow in deciding what to do with basketball in the summer and he signed a contract to coach at Notre Dame that season, earning a 17-4 record.

World War II ended on September 2, but it would take months to process the discharge of a military force of 12.2 million across four continents. Of Georgetown's 11 players from 1942-43 who left with remaining eligibility, six were still on active duty in the fall of 1945, two were in medical school, one was now playing pro basketball, one joined Ripley at Notre Dame (Billy Hassett) and the aforementioned Bob Duffey was killed in action. A team would need to be built from the intramural ranks and from any former athletes who decided to return to campus after they were discharged. First, however, they needed a coach.

The Jesuit moderator of athletics turned to Ken Engles, a senior returning from the Army in the fall of 1945 to complete his studies. Engles was the captain-elect for the 1942-43 team before he was drafted, but had completed three years active duty and was now a civilian. He was the only former player enrolled at the time, and was asked to be a player-coach for a team with no prior collegiate experience.

A total of 50 candidates responded to the call for tryouts and after a week of practice the squad was cut to 16, although 23 different players saw time on the roster over its schedule. Engles favored a roster with a mix of freshmen and veteran talent, figuratively and literally. Freshmen Ed Drysgula and Paul Durkin were prominent in the backcourt, while Engles manned the pivot and a pair of former college athletes in Frank Aires and Pete Baker were dependable options up front.

Aires and Baker arrived on the Ryan Gymnasium court with experiences far more mature than a mere college freshmen. Aires had played basketball at Dayton when he volunteered to join the Army Air Corps, where he flew B-17 bomber missions over Europe and received the Legion of Merit. Baker, a football letterman at Georgetown in 1941 and 1942, joined the Army in 1943 and spent four months in a German prisoner of war camp following the Battle of the Bulge. Baker was one of two former prisoners of war on the 1945-46 roster, but it received no coverage at the time.

Aires and Baker arrived on the Ryan Gymnasium court with experiences far more mature than a mere college freshmen. Aires had played basketball at Dayton when he volunteered to join the Army Air Corps, where he flew B-17 bomber missions over Europe and received the Legion of Merit. Baker, a football letterman at Georgetown in 1941 and 1942, joined the Army in 1943 and spent four months in a German prisoner of war camp following the Battle of the Bulge. Baker was one of two former prisoners of war on the 1945-46 roster, but it received no coverage at the time.Although the schedule listed nine home games, Georgetown really didn't have a home that season. In lieu of renting games at its former outpost at Technical High School, it arranged for its games to be played as part of doubleheaders at Catholic University to save costs. Fifteen of the 20 games overall were local among college and military teams, with road trips to Villanova and LaSalle bookending the beginning and end of the season.

There are few extant records of the 1945-46 season. There is no team photo, no media guide. Without a yearbook produced that year, only a handful of grainy photos survive. After a 4-7 start, the Hoyas won seven of its final nine, with Drysgula leading the team in scoring over six of its final seven. Georgetown won its final five games of the season to finish 11-9.

On March 9, 1946, the Hoyas finished its season with a 54-37 win over LaSalle and returned to Washington on the 10th. The next day, a familiar face arrived at Union Station and took a taxi to campus.

Nearly three years after his Final Four triumph, Elmer Ripley arrived to sign a contract as head coach for the 1946-47 season. Five returning veterans from 1942-43, a pair of transfers from Notre Dame, and the former "Mr. Basketball" from Indiana would be waiting that fall. While none of the members of the 1945-46 team returned to the varsity the following season, they had succeeded in laying the foundation for a return to intercollegiate play.

Baseball and tennis returned in the spring, football in the fall. With as many as 1,000 expected to enroll in the College in the fall of 1946, the students were ready, too.

"Football will do more to boost Hoya morale than anything else, especially if we turn out a winning team," noted one departing senior at year's end. "Making Georgetown co-ed would revive a little spirit, but some of the old-timers couldn't stand it."

That would take a little longer, of course.