The First Four

Can you name a team that appeared in the Final Four in their first and only NCAA appearance? Until 1975, the answer was the Georgetown Hoyas of 1942-1943.

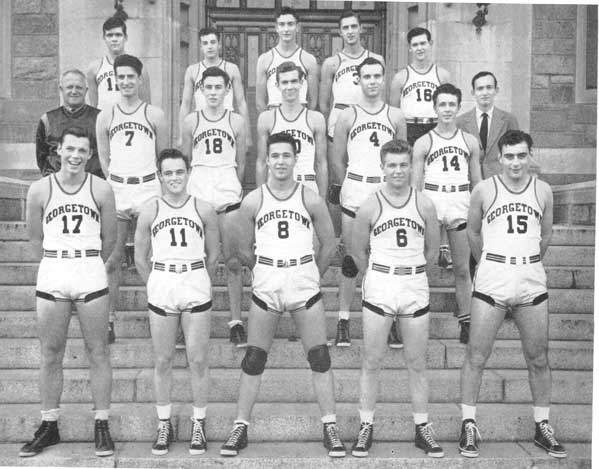

The year was 1943, a most improbable time for a school like Georgetown to assert itself as the preeminent team in Eastern college basketball. World War II had called all but one member of the previous season's 9-11 team to wartime duty, and the campus was under a transformation to a military training facility. With six sophomores, two freshmen, and and one senior for his rotation, few expected Elmer Ripley 's "Kiddie Korps" to actually compete, much less dominate its schedule. It was, in retrospect, the Hall of Famer's finest hour.

The roots of the 1942-43 Hoyas go back even further than many would believe. Step back to 1935, thanks to an Associated Press feature.

"Just as a joke, Elmer Ripley pitted a team of 11-year-old New York youngsters against Temple University's famed championship five at a basketball clinic in Madison Square Garden. The purpose was to demonstrate Temple's zone defense, which had baffled the best collegiate teams.In fact, almost all of Ripley's young men were New York-area high school products, owing to Ripley's recruiting among the area's talent. He had coached Lloyd Potolicchio and James "Miggs" Reilly in a city park league years earlier, and brought DeWitt Clinton HS star Dan Kraus and Lasalle Academy's Billy Hassett to Georgetown in 1941 after seeing them play in summer leagues. Players like Kraus and Hassett led the Georgetown freshman team to a 20-1 record in 1941-1942, losing only to an military squad from the Aberdeen Army Proving Grounds.

What Rip saw made him gasp. The kids passed the ball in, around and through the zone and scored with monotonous regularity. And Temple wasn't fooling.

That was some eight years ago, and Ripley's kept tabs on the kids ever since. When he left Yale, and moved to Georgetown as basketball coach, Ripley sold the young men the merits of higher education at Georgetown.

So today the rare combination of youth and experience is blended in the all-sophomore Georgetown five, a fact which qualifies the Hoyas as one of the two youngest quints in the East.

There's that combination of Danny Kraus and Billy Hassett as breathing proof of the success of the metamorphosis. Rip says Kraus is "the kind of a ball player who makes a team click." Danny, all-New York City selection in the 1939-40 and 1940-41 seasons while at DeWitt Clinton High, was incapacitated much of his freshman season by a bad knee, but he's in his old form now.

Hassett, a neighbor of Kraus in the Bronx, served his basketball apprenticeship at LaSalle Military Academy, Oakdale, Long Island, where he played baseball in addition to basketball. He was named the most valuable player in the 1940 Eastern State tournament at Glens Falls, N.Y.; in 1941 he was named on the all-Eastern team.

And there are many others of the same ilk on the hand-picked squad, many of them the same 11-year-olds who fooled Temple that night. Most are from New York and New Jersey, and all of them are top cream - guys like Lloyd Potolicchio, Don Gabbianelli and Miggs Reilly, to mention a few."

Ripley's final additions were 6-8 New York City star "Big John" Mahnken and 6-9 Ohio native Sylvester "Stretch" Goedde, easily the two tallest men ever to play for Georgetown. Though Goedde left the team for an ill-fated baseball career in Toledo, Ripley had all the pieces in place for a memorable run.

The season started with a comfortable 66-43 win over Western Maryland. In their second game, the Hoyas smashed all local scoring records with a 105-39 win over American--the school's first 100+ point game. The Hoyas took on all comers: Maryland by 10, Penn State by 15, Syracuse by 27. The Orangemen coach Lew Andreas showed no trepidation in calling them "the best team in the East." The Hoyas even managed to avenge the loss as a freshman team to Aberdeen, 48-33, and in a memorable finish, upset the Quantico marines at the base, 54-52. Trailing 52-48 with two minutes to play, the Hoyas tied the game than stole the Marines' pass, allowing Kraus to hit a 15 foot jumper at the buzzer. Legend has it that the Marines were so angry at the college boys for the late steal and buzzer-beater that the Hoyas left the base under armed guard to prevent personal injury by the Marines.

A late season game with a top-rated St. John's team was humbling--the veteran Redmen team rolled to a 65-43 win at Madison Square Garden, knocking the Hoyas from the mythical Eastern title. But the upstart NCAA tournament liked what they saw out of the 19-4 Hoyas, and invited them as one of their four regional selections (over Kentucky and Duke) to the NCAA tournament at Madison Square Garden in March, 1943.

Athletic manager Joe Gardner accepted the bid in lieu of the NIT, saying it would provide Georgetown a chance to meet teams from across the nation instead of the regional nature of the NIT. It was a decision of historic significance.

The Hoyas opened post-season play on March 24, 1943 against NYU, a team which GU had lost 16 of its prior 21 meetings dating to the 1921-1922 season. New York sports writers, underwhelmed by the Hoyas' recent performance at the Garden, proclaimed NYU a 2 to 1 favorite.

John Mahnken, the team's leading scorer, came to play against NYU, scoring 18 of the team's 32 first half points, and Kraus and Hassett's backcourt magic kept the Hoyas going when Mahnken was shut down in the second half. The 55-36 final seemed an upset in every sense of the word, except for Georgetown's coach and his emerging talent, it really wasn't an upset after all.

With the victory over #2-seeded NYU was to be savored, Ripley had no time to spare in preparing his team for the top seeded DePaul Blue Demons. The Demons were coached by rookie Ray Meyer and featured the first great "big man" in college basketball--6-10 center George Mikan. So dominating was Mikan in the first round NCAA game that Ivy champion Dartmouth missed their first thirty-four shots of the game with Mikan's towering frame swatting away shots in the pre-goaltending era.

As odds makers boasted 3 to 1 odds for DePaul and opposing coaches claiming that "DePaul will name its own score!" against the younger Hoyas, Ripley retreated to his Manhattan hotel room to plot a strategy against Mikan and the Blue Demons. The coach stayed up all night and sifted through his nearly thirty years of college and pro experience before he found the defense to thwart big number 99.

The plan, before a crowd of 14,085 on March 25, 1943, involved setting Mahnken on a wing, banking in shots to prevent blocks by DePaul's big man. To keep the DePaul center from rushing Mahnken, guards Hassett and Kraus would congest the middle where Mikan was at his best, allowing Georgetown to get off the shot. The strategy was a double-edged sword--Mahnken could hit his shots but no one could stop Mikan from collecting his. The half ended with a 50 foot shot at the buzzer by GU's Lloyd Potolicchio to narrow the DePaul lead to 28-23.

As Mikan moved outside, Ripley moved inside in the second half, and the Hoyas took the lead thereafter. The lead had grown to 40-36 when Mahnken fouled out with ten minutes to play. At this point, all appeared lost, as Georgetown had no one tall enough to stay with Mikan. Ripley stunned the crowd by bringing in 6-3 Hank Hyde at center to contain Mikan. The thought of sending in a 6-3 backup against the nation's most feared player seemed unthinkable, but Hyde knew better. He had played against Mikan in the high school ranks, and convinced Ripley that he could out-muscle the DePaul center in the pivot.

Coach Meyer didn't pick up on Hyde's entrance as Mahnken fouled out, and sat his 6-11 center down after Mikan connected on the free throws. Georgetown then went on a 5-0 run and when Mikan returned, Hyde had his number. For the last nine minutes of the game, the DePaul All-American was held in check by the smaller Hyde, astonishing the crowd. Hyde gave Mikan nothing but grief, elbowing and jostling Mikan as he did in the Chicago Catholic League. "So just as [he] was about to shoot, I gave him a little push," Hyde told the Washington Post in 1998. "Oh, it's great to be young!"

Across the court, Hassett and Kraus kept the Hoyas moving, winning rave reviews, as was the 11 point career performance by Lloyd Potolicchio in taking the scoring leadership from Mahnken. DePaul closed to seven with a minute to play, and four at the final whistle, but it was not enough. With Kraus dribbling out the clock, a Hoya fan stood up and shouted loudly "Believe it or Not...By Ripley!" , the quote of the tournament. The Hoyas won the NCAA Eastern Regional final 53-49 and were a game from the NCAA championship.

Five days later, Georgetown met Western champion Wyoming for the title. A smaller than expected crowd of 13,206 was evidence of the lack of local interest in the NCAA game, versus St. John's NIT title of a few days earlier. Even cameras were in short supply--the 1943 NCAA title game was the only title game not filmed for posterity.

The Cowboys were led by 6-7 Milo Komenich and a pair of playmakers in Floyd Collins and Kenny Sailors. The two teams were tied at 2-2, 4-4, 8-8, 16-16, 20-20, and 22-22 into the second half before Georgetown opened up a 31-26 lead with six minutes to play.

Georgetown's Kraus and Hassett were sidelined in foul trouble, but substitutes Bill Feeney and Lloyd Potolicchio did their best. despite not being the equal of the duo which had led Georgetown all season.

With six minutes to play, Wyoming went on a 9-0 run, giving the Cowboys a 37-31 lead. Refusing to give up, Feeney connected on an assist from Potolicchio and added a free throw to narrow the lead to 37-34 with two minutes to go. It was not enough, however.

The Hoyas could not score another point the rest of the game, as Sailors and Komenich ran past the tired Hoya defenses and connected on free throws. Wyoming won its first and only NCAA title 46-34, as the greatest season to date in Georgetown basketball history fell two minutes short. Sailors, with a game-high 16 points, was named the MVP of the game.

Despite the end of the NCAA's, it was not the end of the season. The next night the finalists from the NCAA and NIT staged a doubleheader fund raiser for the wartime Red Cross. In the opener, Georgetown defeated NIT runner-up Toledo 54-40, behind 20 from Mahnken, who tried to make up his disappointing 6 point output in the NCAA final. In the second game, Wyoming beat St. John;s 52-47.

The 6-8 center's play late in the season was enough for Look magazine to name him to its All-America team ahead of Mikan and St. John's Bill Closs, making him the school's only first team All-America selection in the pre-John Thompson era. And although there was no such official honor, few would have disputed the recognition of Elmer Ripley as the coach of the year.

The potential of this young team seemed unbounded, but World War II brought an end to further glory. Georgetown discontinued all athletic competition in late 1943, ending the collegiate careers of most of the team and sending Elmer Ripley to Notre Dame in search of a coaching job. The "Kiddie Korps" had served the cause of Georgetown honorably, but most were headed for service of a different kind.

For the 1942-1943 Hoyas, their lives didn't end when their storybook season did. Each in their own way, the 1942-1943 Hoyas went on after the experience of an NCAA title game for their own remarkable lives.

Elmer Ripley was 51 in 1943, but had plenty of coaching left. Too old for military service, Ripley took another job serving as coach at Columbia (1943-44) and Notre Dame (1944-46) before returning to Georgetown in 1946. His first post-war team, made up of many of the stars from 1942-43, finished 19-7 but was not selected for a post-season tourney, but his next two Hoya teams finished a combined 22-30. Georgetown did not renew his contract, but the Ripley was not done coaching. He moved on to jobs at John Carroll (1949-51) and Army (1951-53), then coached the Harlem Globetrotters from 1953 to 1956. In 1956, he served as head basketball coach of the first Israeli Olympic team, and then served as a goodwill ambassador to teach basketball in Israel on behalf of the U.S. Government. Ripley coached the 1960 Canadian Olympic team and was an advisor to the 1972 Canadian team at the age of 82. A month after from Georgetown's first Final Four appearance since 1943, Elmer Ripley died in his home borough of Staten Island at the age of 90.

Among the most notable names of the 1942-43 team was Henry Hyde, a reserve who played in only 11 games but whose defensive play in the DePaul game helped GU overcome the great George Mikan and advance to the finals. Following Georgetown, Hyde became an attorney and was a long time Republican congressional leader from his home state of Illinois, a strong but respectful advocate for the pro-life movement.

After GU suspended its basketball program for World War II, Billy Hassett joined Ripley at Notre Dame, was a second-team All-American, and later played four seasons in the NBA. Hassett later owned a prominent moving company in Buffalo, N.Y.

At 5-7, Miggs Reilly was too small for the NBA, but he stayed in basketball by coaching Georgetown Prep for two years and Catholic University for five more, before becoming a full-time lawyer.

Wartime conscription never allowed Andy Kostecka to reach the Final Four, though he returned and played two more seasons for the Hoyas from 1946-1948. After a brief stint in the NBA, he went into government service, most notably with the Federal Trade Commission.

Kostecka's teammate Danny Kraus also returned to the Hoya varsity after the war, was named a second team All-American in 1947, played briefly in the NBA, and was also in government service, though his work was with the FBI.

Another 1943 teammate, Lloyd Potolicchio, became an Air Force pilot. Potolicchio was killed in a 1966 B-52 crash off the coast of Spain which became known as the Polamares Incident, a little known but harrowing moment in the Cold War where, following the crash, two hydrogen bombs landed on a Spanish village and a third was recovered in a top-secret mission to get to the bomb before it detonated or was located by the Soviets.

Another loss in the service of his country was Bob Duffey, who was killed in World War II. Duffey is the only Georgetown man to have played on both the 1941 Orange Bowl and 1943 Final Four teams, yet was better known as one of Georgetown's outstanding students. Since 1955, the Robert A. Duffey Memorial Award has been presented annually to Georgetown's most distinguished scholar-athlete.

The most notable of the 1942-1943 Hoyas was 6-8 All-American John Mahnken, who left college for the pros decades before Allen Iverson thought about it. Too tall for the military, Mahnken left Georgetown and teamed up with Arnold "Red" Auerbach and his pre-NBA Washington Capitols in 1945, one of the the decade's most prominent pro teams. Mahnken played later NBA basketball with a variety of teams through 1953, ending his career with Auerbach's Boston Celtics. The 1957 Georgetown Alumni Catalogue listed him as "missing", and he remained so until 2001, when a reader to this web site reported him living in a veterans home in Maryland. Mahnken died later that year.

More names followed, as with the march of time. Miggs Reilly was the last surviving member of this band of brothers, whose efforts remains among the greatest stories in the rich tradition of Georgetown University and its student-athletes.

Believe it.