1981-82 Season In Review

What was the 1981-82 season really like? Don't start in New Orleans, start in Anchorage.

The only college game Patrick Ewing did not start was his first, where the #5-ranked Hoyas fell unceremoniously, 70-61, in the opener to the 1981 Great Alaska Shootout (or, as The HOYA put it, the "Great Alaska Wipeout"). The Hoyas dropped two of three in the tournament, falling to Ohio State 47-46 two days later.

Following Alaska, Georgetown went on a 12 game win streak, with a key intersectional matchup with San Diego State marking the Hoyas' first appearance at its new home at Capital Centre. The game drew just 8,503, where the Aztecs shot just 36% and committed 37 fouls, sending the Hoyas to the free throw line 53 times.

Georgetown placed four in double figures, led by 21 from Eric Floyd, while the Aztecs' Michael Cage was held to 3-12 from the field.

Georgetown's first national TV appearance on CBS since the 1970 NIT was a rout, as the Hoyas took a seven point second half lead into a 24 point win.

Leading 46-39 with 13:05 to play, Eric Floyd scored 10 of his 27 points in a 20-2 run that put the game out of reach, as the Hoyas shot 59% for the game. Five players were in double figures, including 12 from Anthony Jones, 11 from Fred Brown, and 10 each from Mike Hancock and Patrick Ewing. Patrick Ewing's debut at the Garden was the stuff of legend, as the Hoyas so thoroughly overwhelmed the #20-ranked Redmen that St. John's coach Lou Carnesecca called four of his five time outs in the first half to halt the run, but to no avail. Georgetown led by as many as 31 in the first half, 42-9, and coasted to the win.

Georgetown was led by 16 from Eric Floyd, as the Hoyas owned the boards, outrebounding St. John's 43-21 in the game.

The freshman star for the Redmen, Chris Mullin, was 0-6 from the field.

After a three game losing streak, questions were raised if Georgetown had the mettle to contend in February. They answered with nine wins in their final 10 regular season games.

Among the road wins, none were as impressive as an 83-72 win at Villanova, a week after a 16 point win over the Cats at Capital Centre. Eric Floyd's 29 point effort, one short of his career best, earned him commendation as the best player at the Palestra that season by the Philadelphia sports writer corps.

Georgetown was on a roll. Following Villanova, the Hoyas routed Seton Hall 113-73, then followed it up two days later with a 17 point knockout of Syracuse.

In a game that combined for 49 personal fouls and 60 free throws, Georgetown outscored the Orangemen 17-4 to end the first half, erasing a five point Syracuse lead. The Hoyas prevailed behind 27 points from Floyd, 22 points and 13 rebounds from Ewing, and 15 points from Eric Smith

In the days before ESPN took over college basketball, many fans still looked to the NBC Game of the Week to see the best talent in the sport.

Georgetown's 63-51 win over #4 Missouri further burnished the rising national reputation of freshman Patrick Ewing, with 13 points, 13 rebounds, and a missed dunk that NBC replayed three different times for effect. Overall, GU's defense shut down the Tigers, and the raucous home court advantage hadn't been seen before--or since.

After four straight games holding opponents under 50 points, Georgetown gave up 54 to Villanova, but nonetheless won its second Big East championship in three years, defeating the #1-seed Wildcats 72-54.

Tied with 16 minutes to play, the Hoyas outscored the Wildcats 22-5 to pull away, ending Villanova's eight game win streak since losing to GU on Feb. 3.

Eric Floyd (17 points) was named the MVP, as GU held its three Big East opponents to just 18 second half baskets for the tournament.

Georgetown's first game in the 1982 NCAA tournament may have been its most difficult.

Despite 18 turnovers and a sub-par effort from All-American forward Bill Garnett, the Cowboys never gave up, closing to 46-43 with 1:34 left behind center Chris Engler. Eric Floyd answered with a late basket and a foul, and Eric Smith added two at the line to seal the win.

The Hoyas moved on to Provo, UT, defeating Fresno State, 62-48, to advance to the regional final.The battle between #4 Oregon State and #6 Georgetown wasn't really a battle at all.

The Hoyas shot a school record 74% from the field (29-39), pulling ahead early and never looking back, to earn the Final Four invitation from the Western Regional. GU led by 18 at the half, and was led by 22 points from Eric Floyd and 13 from Patrick Ewing.

"I would have to say it was the best performance by any team I've ever coached," said coach John Thompson.

The best was yet to come.

Before 61,612 in attendance (the largest crowd to date in the history of college basketball), the Georgetown Hoyas earned a hard fought win in the 1982 national semifinal, in a 50-46 defensive struggle against the Louisville Cardinals.

Two years removed from their 1980 national title (and a year from a third Final Four in four years), the Cardinals entered the game as a high-flying offensive team, with four seniors from its 1980 title team: Jerry Eaves, Wiley Brown, Derek Smith, and Poncho Wright. Shooting 50 percent for the season and 59 percent in NCAA tournament play, keeping the game close was a priority for a Georgetown Hoyas team which had won nine straight, eight by double digit margins, but had not faced a team of Louisville's caliber to date. From the outset, defense would set the tone.

The semifinal was the finale of the doubleheader, following a game where North Carolina took a big lead early on Houston and ran away with the win. Neither team would run away with this one.

A trio of Louisville defenders--Charles Jones, Wiley Brown, and Scooter McCray--each took their turn at crowding Patrick Ewing and limiting his impact inside. Georgetown, which had shot 74 percent in the regional final over Oregon State, was anything but in the early goings. In the first six minutes, the teams combined for 12 points, with Georgetown holding an 8-4 lead. Every shot was contested. Every pass, too. The teams combined for 23 turnovers in the first half alone.

Georgetown's ability to stay in the game would fall to the outside. With Ewing bottled up inside and the score tied at 12, Georgetown scored six straight, including consecutive baskets by freshman Anthony Jones to extend the lead to six, 18-12. The Cardinals responded with a 6-2 run to close to 20-18. Each team scored a pair of baskets to close the half with Georgetown up two, 24-22, as the Hoyas held Louisville to 37 percent shooting at the break.

Louisville picked up the pace to open the second half, outscoring GU 8-5 over the first five minutes of the half and taking a 30-29 lead. The Hoyas retook the lead on a pair of free throws, but it seemed that neither team had the knockout punch.

Floyd picked up his fourth foul midway in the half and it was a fellow senior that stepped up. Eric Smith scored eight straight points to push the lead out midway in the half. Wrote the Associated Press:

"Then Smith took over. He scored two baskets before Floyd picked up his fourth personal... Smith then hit another basket and pair of foul shots and Ewing capped the run with two free throws that made it 43-34 with 5:30 to play."

"I don't know where they were putting their defensive emphasis," Smith told the Washington Post, "but I was able to find the creases...We always try to get the ball inside to Pat, but they were sagging on him and he was having a little trouble. So I just took the open shots when Louisville gave them to me."

The teams exchanged baskets over the next three minutes, with the Hoyas leading by nine, 47-38. Louisville's pressure defense forced the Hoyas into mistakes, with Fred Brown coughing up a turnover in one and missing the front and of a one and one on another, whereupon the Cardinals rallied to close to 47-42 inside two minutes, and 47-44 following free throws with 1:08 left. For Georgetown fans who had seen the Hoyas fail to hold a second half lead to Iowa not two years earlier, tension was in the air.

The Cardinals opted to foul Brown at the 44 second mark. Brown made both, 49-44, and the Hoyas looked to be in winning form when Louisville missed a quick shot, but Brown lost the ball and Derek Smith hit a jumper with 13 seconds left, 49-46.

Eric Smith was quickly fouled. A collective gasp sailed across the Superdome when Smith missed the front end of the one and one, only to see Louisville lose the ball out of bounds. The Hoyas got the ball into Floyd, who was quickly fouled. Floyd made the first, 50-46, but missed on the second, as the Cardinals raced down the floor for a late basket. Falling short, the Hoyas escaped with the 50-46 win, albeit the most points it allowed in an NCAA tournament game to date this season.

I can't remember us playing so poorly offensively and winning since I've been at Georgetown," said tenth year head coach John Thompson. " We had to strain for everything we got. You have to attribute our poor offensive game to Louisville's defense."

They've got great quickness and that intimidating big man," said Louisville coach Denny Crum. "We didn't play well enough to win."

Smith (14 points) and Floyd (13) were the only Hoyas in double figures. Georgetown shot 43 percent from the field, 70 percent from the line, but three of its six misses came late. Ewing finished with eight points, ten rebounds, and only two fouls in 37 minutes, which forced Louisville to expend a lot of defensive energy inside. The Cards shot 39 percent for the game, 42 percent in the second half, but were outrebounded 34-27. Georgetown was able to keep Eric Floyd on the court with four fouls, but the Cardinals lost Rodney McCray to fouls late, limiting its comeback.

Ten seasons removed from its crushing 3-23 season, Georgetown advanced to the national final Monday against top seeded North Carolina. As thousands of Georgetown fans filled the French Quarter in the humid New Orleans evening, the team itself was on a bus to Biloxi, MS. Thought by some sports writers to be a motivational ploy, the real reason for 1982's "Hoya Paranoia" was anything but.

The day following the Louisville game, John Thompson told a press conference that Ewing had received a death threat in a call made to the University in the days before the NCAA tournament. The team opted to stay in Salt Lake City rather than in Logan and Provo for the Western Regional games, and passed on the expected location of the Marriott Hotel on Canal Street for security reasons. Thompson did not inform the team of the specific details until after the Louisville game, but arrived with Ewing at the Sunday press conference with a bodyguard for the freshman center.

"[The caller] said he wanted to advise Patrick that he would be killed," said Thompson, "When I was told, it scared the hell out of me."

"I've been criticized in the media for shielding Patrick Ewing," Thompson said. "Only I knew what this highly publicized, highly recruited 18 year old has been through in the past year. If you did, you'd know why I'm protective."

"I have the responsibility to parents to protect their sons who play for me. I want to win this national championship, want it badly. But first I'm concerned with my kids well being...I'm telling [about] this death threat story now because I have a tremendous forum, reporters from all over the country. I think it should be known why I, as a coach, feel a need to watch out for the young men in my care."

"It's about over now," Thompson said. "After [Monday], Ewing will not be in a public situation for a while."

Instead, it was only the beginning for a lifetime in the public for Ewing, beginning with a game that would rank among the greatest in the history of the sport.

In nearly 75 years of NCAA tournament basketball, there have been three truly transformative games. Three.

On March 23, 1957, North Carolina won its first NCAA championship in a 54-53, triple overtime win at Kansas City's Municipal Auditorium. The game itself was a classic, not only for its duration, but for its reach. Only 10,500 attended the Saturday night event, but thanks to a Washington television producer named C.D. Chesley, it changed basketball forever.

Chesley saw the final two games of the tournament, years away from its Final Four moniker, as a great opportunity to reach the emerging TV audiences back in North Carolina. He lined up three TV stations, sold advertising time, and rented production equipment at no small expense to show the games back to North Carolina, which ended after midnight on the East Coast. The response was epic. When the Tar Heels returned home, 15,000 fans greeted them at the Raleigh-Durham airport, all because of TV. For two generations, the Chesley Network offered regular broadcasts of ACC games from Washington to Columbia, dutifully sponsored by Pilot Life Insurance, and television discovered the power of regional college basketball.

By 1979, however, college basketball was still a novelty at the national level. The ACC region had fallen in love with the game, but basketball was as still a hit or miss thing in many markets. NBC had bought annual rights to the NCAA tournament in the early 1970's but committed only to show the semifinals and finals nationally. Despite the bright lights of UCLA, Kentucky, Indiana and many great teams of the era, NCAA basketball was an afterthought.

On March 28, 1979, that changed. The 1979 Final Four had all sorts of interesting stories, from the first Final Four for Ray Meyer's DePaul Blue Demons in 36 years, to the unlikely of entrants in Ivy champ Pennsylvania. But the national press zeroed in on the NCAA final between Michigan State, a Big 10 power with a charismatic sophomore named Earvin (Magic) Johnson, and Indiana State, still an unknown of sorts in college circles but undefeated all season, led by a rural wonder cut from Hollywood central casting: Larry Bird. While the game itself was somewhat less than memorable, the star power of these two collegians aligned the nation's attention to this weekend on the NCAA calendar, and the ratings have never been topped since: it remains the most watched basketball game (college or pro) ever in American television history.

Another phenomenon was born. In 1973, NBC was paying $1 million a year to broadcast the tournament. Now, just a year after the Michigan State-Indiana State game, emerging popularity pushed that number to $9.8 million a year to the NCAA, a huge sum for a college event. The following year, CBS shocked the sports world by outbidding NBC by 60 percent to broadcast the NCAA tournament in a multi-year deal which would pay as much as $26 million in the last year of the contract. "Before yesterday," wrote the New York Times, "CBS had not had a major television contract with the NCAA for almost two decades, since it televised a football game of the week in 1963." The latest iteration of that CBS contract begun in the 1981-82 season was renewed in 2010 for 14 years and $10.8 billion.

CBS had the venue. They would soon have the masterpiece that would define the championship game for the next 30 years, and it took place March 29, 1982.

"It's hard to describe how unique this game really was, whether to those who weren't there or to those who never saw it live on TV," said a note on this site in 1999." It was an era when Georgetown was the underdog, the school people cheered for, not against. Its sky-blue uniforms and sky-high enthusiasm permeated the nation that weekend, with as many as one-third of its [undergraduate] student body on an unofficial spring break to the French Quarter. Some alumni even came to the game in formal wear, as if to recognize a gala performance. With five future NBA all-stars on the floor and two coaching legends on the sidelines, the game did not disappoint."

If the 1979 Final Four seemed right out of a movie script, the 1982 final was even more intricate. The top seeded North Carolina Tar Heels (31-2) were no stranger to NCAA tournament play, having made the Final Four six times since 1965 under coach Dean Smith. But in Smith's 20 years at the helm, the Tar Heels had never won a title. Smith was labeled a "choker" by some in the regional press as a result.

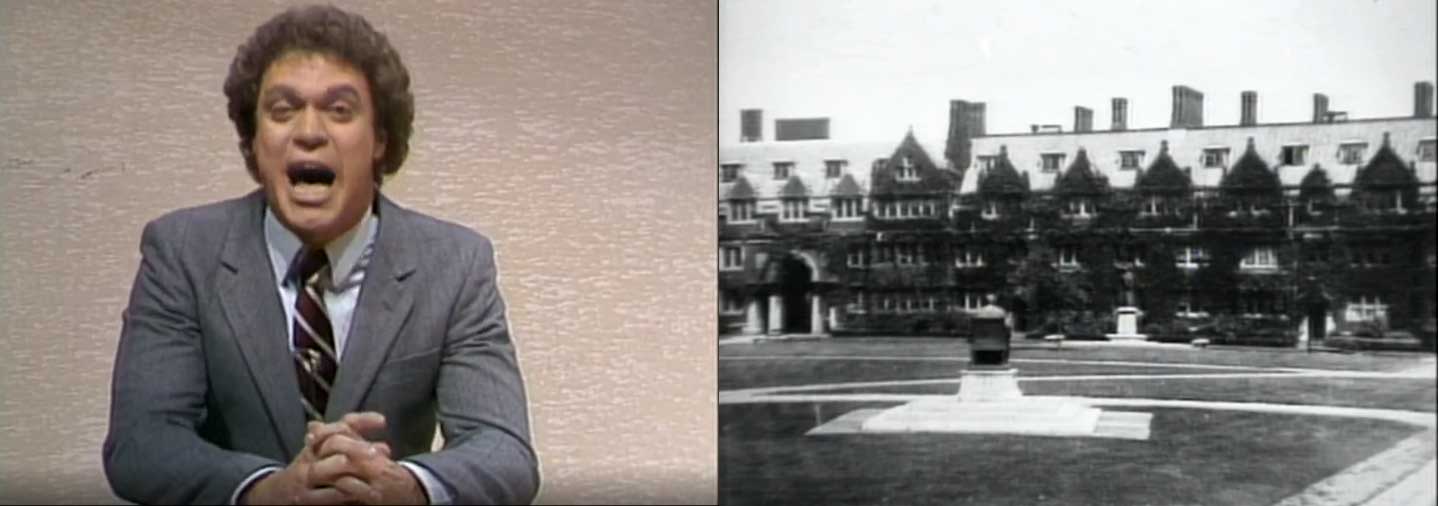

Smith's opponent was an unlikely entrant, a 30-6 team at a school better known for academics than athletics. When Saturday Night Live's Joe Piscopo sought to characterize the two schools, his staccato sportscaster character whipped through a series of attributes on the strength of North Carolina.

"Who is the better team? Let's take a look," Piscopo said. North Carolina?...Good offense! Tenacious defense! Great coaching!"

"Georgetown?....Fine law school! Great dorms! Incredible coeds!"

(For what it's worth, NBC had three photos of the Tar Heels as backdrop for the first part of Piscopo's comedy bit, but nothing of Georgetown, relying on what appeared to be stock photos of the University of Pennsylvania in its place.)

The pre-game intrigue was more than that, of course. The sheer size of the event and the talent seen in the semifinals had elevated the national interest in the final to heights not seen since Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, now the emerging superstars in the NBA, faced off three years earlier. Suddenly, the Final Four took on the national interest normally reserved for a Super Bowl, and in a stadium which had hosted two Super Bowls in the past five years, the media confluence seemed all but inevitable.

There was Dean Smith's Final Four near-misses, Smith's friendship with Georgetown's John Thompson, the novelty factor of Georgetown, a newcomer on the national stage, with the growing national awareness of a future star in Patrick Ewing. Through it all, the game delivered. The 1982 championship game changed the way these games are seen. It was no longer a game, but a spectacle.

No longer were places like Kansas City's Municipal Auditorium or even Cole Field House able to host the championship. The NCAA moved the 1982 Final Four to a place basketball had never imagined: the Louisiana Superdome, the then-largest domed structure on earth. The 1982 Final Four would sell out this amazing building: 61,612. Excepting a 1951 Harlem Globetrotters exhibition in West Berlin, it would become the largest crowd ever to witness a basketball game. The uppermost seats in the building stood 19 stories tall and were 375 feet from the court. It didn't matter. Every seat was taken.

An audience estimated at 31 million tuned in for the show, and Act I opened with wonder. Thompson had told Ewing to set the tone inside by blocking the first six shots of the game, no matter what, in part to avoid the chance for Carolina to pick up early points on the run. Two blocks and four goaltends later, the crowd marveled at the reach of the freshman center. Georgetown had arrived on the big stage, and the audience settled in for a battle across the floor of the Superdome.

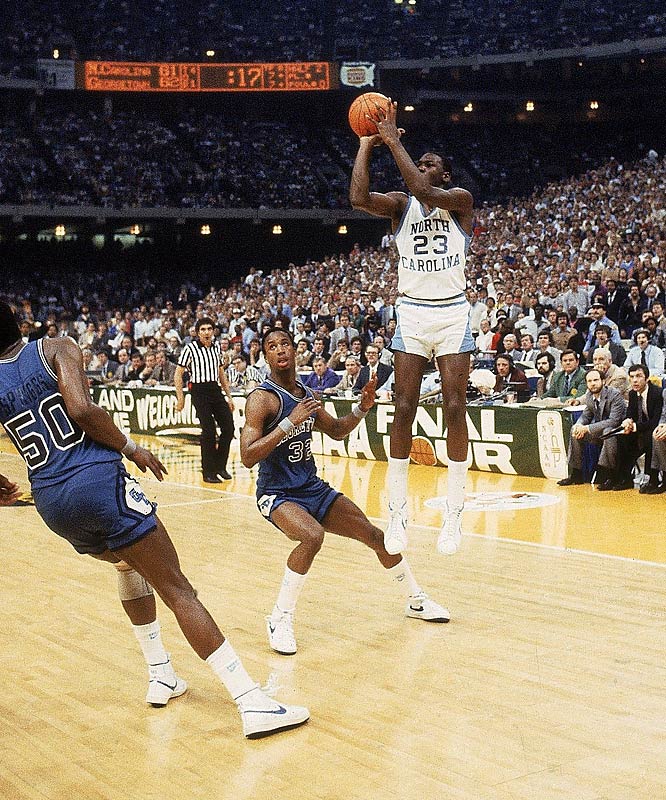

Georgetown's 12-6 lead seven minutes into the game was the largest lead of the game, and no team led by more than four for the rest of the game. The lead changed six times over the course of the first half, as the Tar Heels were led by a junior forward from Gastonia, NC in James Worthy and a freshman from Wilmington, NC gaining praise in ACC circles, but still unknown to much of the nation: a 6-5 guard named "Mike" Jordan. Georgetown answered with its own Gastonian, Eric Floyd, and with "Pat" Ewing in the middle, the teams volleyed back and forth. Worthy scored 12 of his 28 points in a first half run, but Georgetown held a 31-30 lead at the half--both teams were shooting over 50 percent between them.

The lead continued to change hands in the second--nine more times, in fact. A Ewing tip-in was met with a Worthy dunk; a Floyd jumper was matched with an outside shot from Jordan. Eric Smith would drive inside, and Sam Perkins would follow suit. Only in later years would fans realize the level of talent on the floor that night, and the epic battle to follow.

The second act was a heavyweight battle. Georgetown had maintained its halftime lead through much of the opening minutes of the vesper half, playing to its strengths on defense and using Ewing as an option inside. UNC made its run with 11:52 to play, when Worthy dunked over Floyd and picked up the basket and foul, 53-52. The teams held each other without a point for over three minutes in this era without the shot clock, until Worthy went inside for a second dunk and gave UNC a 54-53 lead with under eight minutes remaining. On the next series, Ewing went inside and dunked it over Perkins, 55-54.

Georgetown held Carolina on its next possession and Ed Spriggs added two free throws, 57-54. Carolina muscled inside, picking up free throws on its next three possessions to go up 59-56, with Ewing picking up a key fourth foul in the process. Thompson opted to keep Ewing in for the remainder of the game.

On the next series, Brown drove, was fouled, and connected on free throws. Now 59-58, Smith began to slow the pace of the game to the Tar Heels' liking. With 3:25 left, Jordan entered the lane and took a high arching jumper over Ewing, 61-58. A minute later, Ewing went inside with a jumper of his own, 61-60. It would now come down to one or two possessions per each team, and the tension was undeniable.

Act III of the drama began in the final two minutes. With UNC in its famous "Four Corners" spread/stall offense, still up one, forward Matt Doherty was fouled by Georgetown's Eric Smith with 1:19 remaining, still up one at 61-60. Doherty missed the front end of the one and one, and the Hoyas were back in business. Thirty two seconds later, Floyd hit a jumper in the lane, and Georgetown had taken the lead, 62-61. "Very suddenly," wrote Phil Musick of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "there was no time to employ the Four Corners."

UNC's Dean Smith, not known for calling time outs late in games, did so at the 0:32 mark. Smith drew up two plays, one for a man to man defense if employed by the Hoyas, one for a zone defense. He recalled later that "I had a hunch we could wind up with Jordan as the shooter if the Hoyas were in a zone."

Georgetown returned to the zone.

Guard Jimmy Black set up the play and spotted Jordan on the left wing, who shook off Georgetown's Eric Smith and got open for a second. Black fired the pass to Jordan, who let loose a 15 footer with 17 seconds remaining. Jordan remarked after the game he had thought about a shot to win the game all weekend, and was determined to do so if given the opportunity.

"The play was designed for Mike to shoot the jumper," said Black. "They were in a 1-3-1 some and he should have had about a 15-foot shot after we passed it a couple of times."

With the birth of the Michael Jordan legend, the Tar Heels had retained the lead, 63-62, but the Hoyas would have one last chance.

Two concurrent events were in play in those fateful seconds. First, Georgetown did not call a time out, hoping to keep UNC away from setting up a defense for the final play and have enough time for Brown to bring the ball up the court, look to Ewing down low or Floyd gain position as he had done all season. As a result, UNC was not in a matched-up defense and its players were not in the correct position on the court--James Worthy, for instance, had not returned to the pivot where Ewing was setting up or to block Floyd from making a cut to the wing.

"We could have called timeout and set up a play, but I wouldn't have known what kind of defense Dean was going to use," said Thompson. "So I would have wasting my time setting up a play." Second, Brown brought the ball to half court with under 10 seconds remaining, and something happened. No, not that.

"I picked up my dribble, and that killed it," said Brown. "At that point, I should have called time out. But I saw Eric [Floyd] open on the left baseline. But they over played, so I looked for Pat."

Ewing was covered inside by Perkins, who had moved over in Worthy's absence.

"But I decided to pass it to Eric Smith, who was on the right side of the lane. I thought I saw Smitty out of the right corner of my eye.

"It wasn't him."

This epic performance was soon halted amidst one of the most jarring pieces of drama ever seen in sports.

Brown's lateral pass landed in the arms of Worthy, who stood stunned for a moment, then proceeded to drive down the court as the crowd took note of what had apparently happened. Many fans were so far away in the Superdome that they only noticed that the lower level of the crowd had suddenly stood and pointed in the direction of the play; there were no video screens anywhere in the building. Unsure whether to drive for the basket or run out the clock, Worthy veered away from the basket and was fouled by a trailing Eric Smith with two seconds left.

So began what seemed like an eternity as the Superdome crowd and TV audience gathered its breath, looked upon the exhilaration and relief at the realization of Dean Smith's first title in seven tries, yet quickly drifted its attention back across the court, where the weight of the sports world had descended upon Brown's 20 year old shoulders. Wandering in the direction of the bench, Thompson took sight of Brown and hugged him.

Worthy, who had committed a similar turnover in the first half that is all but forgotten today, commented on why he was where he was.

"I saw the ball coming up court, I would have followed [Ed] Spriggs, but I had a feeling, it was an instinct. So I saw [Brown] faked, so I came right back out...I really thought he saw me and would try to bounce pass it by me or throw it over my head."

A crestfallen Eric Floyd recalled that "[Brown] was passing the ball to me, but I had cut away from him and to the corner."

"The first person we look for is Floyd," Eric Smith said. "But there was no set play. I was there at first, and I called for the ball. I guess [Brown] heard my voice and thought I was still there."

There is also a body of opinion that the uniform color affected the play, perhaps subconsciously.

Entering the final, Georgetown had wore its white home jerseys each of its four prior NCAA games and 12 of its last 14 games dating back to a February 2 game at the Palestra, before being designated the road team in the final. If Brown had grown used to seeing his teammates in white with blue numbers, the split second decision with someone in the forecourt wearing white and the blue number 2 (not Eric Smith's 32 or Gene Smith's 22, but Worthy's 52) might have played a role. But Brown never made an excuse.

"My peripheral vision is pretty good, " Brown told the Washington Post. "This time, it failed me. It was only a split second. But, you know, that's all it takes to lose a game. I knew it was bad as soon as I let it go. He didn't steal it, I gave it away."

Worthy's run down the court was crucial in another respect--the game was not over, even though many thought it was. Sent to the line, Worthy, who was only 2 for 5 at the line in the game, missed the first, then missed the second. Georgetown got the rebound, but just two seconds remained. Eric Floyd threw a 50 footer, which fell short. Had there been another second, maybe another five or ten feet closer, the ending very well could have been different.

The epilogue was a wild swing between the exhale of the Carolina fans and the stunned response from Georgetown's faithful. This was not the foul without time on the clock seven years earlier in Tuscaloosa, it was not even the three point play two years earlier in the Spectrum that erased a 16 point halftime lead. This was different. One possession from a chance to win the national title, it was suddenly all gone.

Thompson made it a point take Eric Floyd to visit the UNC locker room after the game. It was not easy for either, but Thompson paid Smith the respect of a hard fought game.

"Fred Brown sat at his locker and answered every question. It couldn't have been easy," wrote Michael Wilbon, then a 23 year old from Northwestern University who had joined the Washington Post staff two years earlier. "About 30 of the more than 100 reporters surrounding Brown thanked him for answering the questions. Many shook his hand.

"How can you be so composed?" someone asked.

"This is part of growing up," Brown said.

College basketball was never quite the same after this game. Neither was Georgetown basketball.