Crossing The Line

April 3, 2019

In 39 years of following, supporting, and covering Georgetown basketball, it remains the most evocative moment I have ever witnessed with this program.

On March 27, 1982, armed with a HOYA press pass and a second row seat for the national semifinal between North Carolina and Houston, I took my place among writers and media figures far more versed in the sport than a 19 year old would ever be. Seven minutes into what was becoming a sizable and somewhat boring lead by UNC amidst a cavernous 61,612 in attendance that day, press row at the Louisiana Superdome was startled at what appeared to be something going on along the Girod Street entrance of the building, at the time the largest indoor structure in the world. Sitting at approximately the 50 yard line of the building, writers were craning their necks to see what was going on.

The noise was a low roar, one that could be heard across the stadium, so much so that even players on the North Carolina bench were looking in that direction.

As I turned, I saw three full sections of the Superdome seating in the end zone, sections 126 through 128, standing. It was the Georgetown section, the section where I would be watching the semifinals later that afternoon. They weren't yelling or trying to get on TV. They stood and applauded.

They stood and applauded a 40 year old man who had walked out the tunnel and, without an entourage, proceeded to walk the 20 or so yards to the folding chairs where the Georgetown pep band was setting up, to sit down and watch the first half of the UNC-Houston game.

They stood and applauded John Thompson, and it wasn't until years later I fully understood the magnitude beyond the moment - not merely for him, but for the school he represented.

The story of Georgetown University has long been that of contrast: of Catholic and non-Catholic, of rich and poor, of blue and gray. "Utraque unum", as the saying goes. The 1960's brought a new dynamic to this story: of white and black. There is no small irony that for sportswriters of who once referred to Georgetown as "Black America's Team", or for those who will tell you they thought Georgetown was a historically black college from watching the Hoyas on television, this University was anything but. If any school would be chosen in the 1980's to assume this unique place in the national dialogue of race, athletics and society, Georgetown might have been the least likely of them all.

Georgetown was in the city of Washington, but was not of it. A northern institution in a mostly southern city, a symbol of privilege as parts of the city languished in poverty, and as a school unattainable to many of its residents, Georgetown remained distinct from the city of its birth, which had become a majority black city in a period of economic and social transition.

By contrast, it seemed that every other Catholic school of that era used athletics, particularly basketball, as a sign of opening its doors to black students to achieve on and off the court, versus those schools that visibly did not allow them to do so. In San Francisco, it was Bill Russell and K.C. Jones; at Creighton, it was a basketball star named Bob Gibson who turned his attention to baseball and is considered one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history.

At Loyola-Chicago, it was Jerry Harkness, at Marquette, Dean Meminger. Every school had a breakout star, it seemed: Sihugo Green at Duquesne, Tom Hawkins at Notre Dame, Wali Jones at Villanova, Cliff Anderson at St. Joe's, all of whom sent a larger message about the power and promise of education for all.

There was no Bill Russell or Jerry Harkness at Georgetown, however. The largest Catholic university south of the Mason-Dixon Line, it consciously avoided the issue of integration while the issue was growing externally in importance and resolve across the country. Athletics, a visible face of the University, reflected this approach.

At one time, it was deemed acceptable. Soon, it became indefensible.

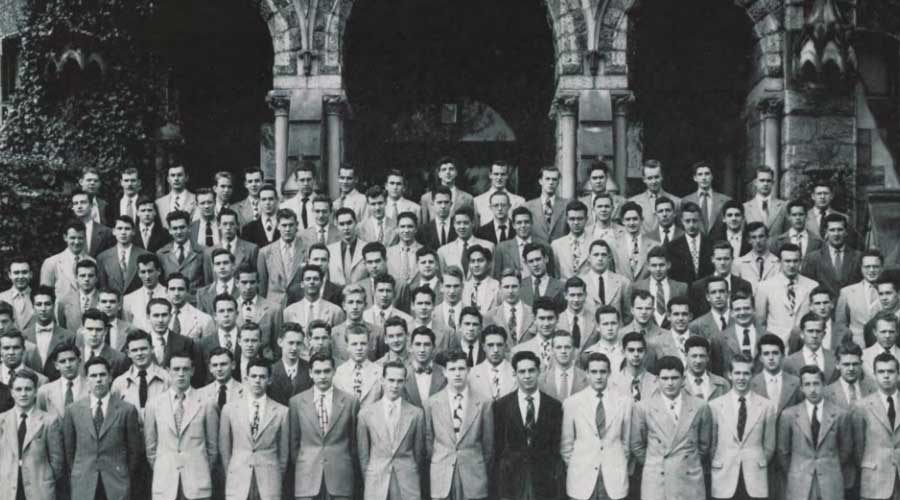

For its first 150 years of existence, not a single African-American had even attended, much less graduated from, Georgetown University or its associated professional schools. In 1947, with the post-war enrollment of the College expanding from 356 to over 1,400 students, University President Rev. Lawrence Gorman, S.J. asked each of the schools to add black students to their upcoming classes, but his fellow Jesuits were slow in their response. The first black undergraduate was not accepted until 1950 when Samuel Halsey (F'53) joined the School of Foreign Service. A handful of law and medical students followed in 1950. The first black student in the Nursing School was not admitted until 1952, and left within a year. The Dean of the College, Rev. Charles Coolahan S.J., did not act on the request.

"All the [original] black students were enrolled in the evening division," said Charles Curran, a former Jesuit who authored a three volume history of the University beginning in 1985. In a 2012 interview, he told The HOYA "I dare say your typical Georgetown University undergraduate did not know African Americans were attending [the school at that time]."

The 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision of Bolling v. Sharpe desegregated Washington's public schools, but not necessarily its private ones. Georgetown College would not enroll an African-American until 1962, even after accepting a pair of African exchange students a year before Harry Campbell (C'66) began his studies. By 1969, progress was slow--there were just 30 black students in a undergraduate population of over 4,000.

Curran's history does not look kindly upon the term of Rev. Edward Bunn, S.J. in this regard. Bunn, a Maryland native who served as Georgetown's president from 1952 to 1964, did little to integrate the College during his tenure as president. In 1946, it was Bunn who, as president of Loyola College in Baltimore, rejected integrating that college, citing fears of violence by faculty and alumni if he proceeded. (The school was integrated without incident in 1949 after Bunn left for Georgetown.)

The undergraduate schools in particular saw no need to change admission requirements to accommodate anyone. While Georgetown was less competitive for admissions as it is today, the Jesuits offered little leeway if any student, white or black, did not have acceptable grades, and athletes got no special treatment in this regard.

A coach's protestation notwithstanding, local basketball recruits got no second looks, white or black, and many went on to success elsewhere.

In 1950, Gene Shue was an all-city standout at Towson Catholic, but was wait-listed at Georgetown and was never moved forward to admission. Frustrated, he enrolled at Maryland that fall as a walk-on. Shue became an college All-American and a five time NBA All-Star.

In a 1968 interview with athletic trainer Raymond Medley, Medley insisted that "Elgin Baylor walked through the Georgetown gates [in 1954] and the school officials told him that he couldn't make it academically. So he went to Seattle and became one of the greatest ever to set foot on the basketball court."

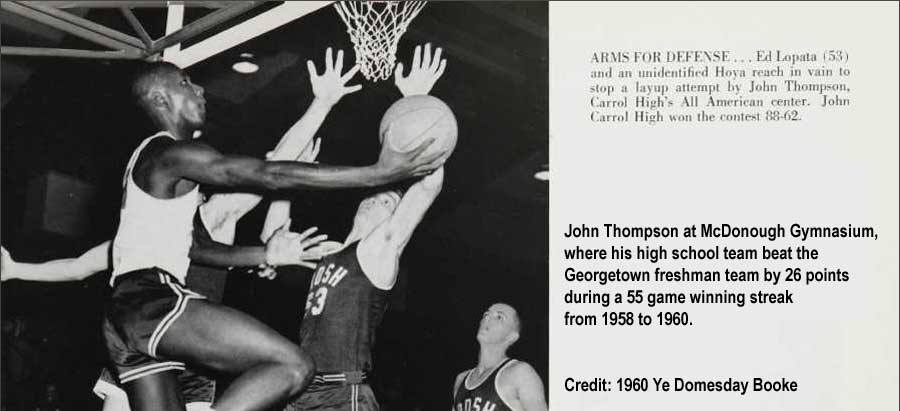

Another example was John Thompson, the 6-10 All-American who attended Archbishop Carroll HS, the first integrated Catholic high school in the city and who played some of his high school games at McDonough Gymnasium. Thompson's grades from Carroll admitted him to Providence, but the Archbishop's own university didn't agree. Tommy Nolan, the basketball coach at the time at Georgetown, remarked that Thompson was an excellent recruit but that "it would have been difficult for him here. Maybe I was just a little too idealistic, but I didn't want him to get hurt."

At Providence, Thompson led the Friars to the 1963 NIT championship and the college's first NCAA appearance in 1964 with a 26 point, 14 rebound average. In the same three seasons, the Hoyas failed to earn any post-season invitations.

"Let me tell you who we've lost," Medley said. "Bob Whitmore, Sid Catlett, Austin Carr, and John Austin are all from around the Washington area. They're all playing basketball for other colleges, and well too. They leave here and later come back to dominate us." Austin played alongside Thompson at Carroll and was a two time All-Met star at DeMatha who was passed over by Georgetown and enrolled instead at Boston College. In his senior season, he torched Georgetown for a 49 point game in 1964 that eliminated GU from NIT consideration and remains a Georgetown opponent record to this day.

It did not go unnoticed outside the gates that Georgetown's athletic teams were not integrated. From 1956 to 1961, Georgetown was invited to play in four holiday basketball tournaments in the Deep South where segregated teams were the rule and Georgetown was a dependably all-white team. Coach Tom O'Keefe chose to move the club away from southern tournaments after 1961; his team achieved its most memorable tournament performance not in the South, but in Philadelphia, upsetting #1-ranked Loyola Chicago in the 1963 Quaker City Classic.

By the mid-1960's, Georgetown was becoming an anachronism. Not its teams, but the University.

"Why are there not any Negro basketball players at Georgetown?" asked a reader to The HOYA in 1965. "Certainly there are Negroes who qualify, both academically and athletically. One need look no further than the D.C. Metropolitan area to see this is true. Is it the coach or the administration at this 'Catholic' institution who is lacking in Christian charity?"

In response, the newspaper noted that "we haven't grabbed any of the stars from the metropolitan area's talent gold mine, white or Negro. Some cite local coaches' displeasure with the development of basketball talent at Georgetown as the reason for the complete shutout...however, one should [also] realize that Georgetown has an odd approach to the big-time, whether in basketball or [academics]."

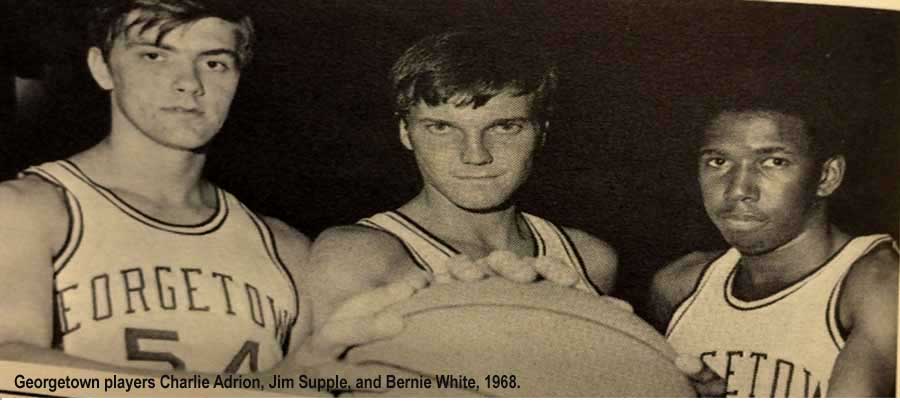

In that same year, O'Keefe worked to bring the school's first black player to the basketball team. He recruited Bernard White (B'69), a 6-2 guard from Fairfax, VA, who was not only a good player but the president of his high school class, a member of the National Honor Society, and had already completed a semester of college credits at George Mason College, giving the admissions office little room to question his credentials.

"The only black player on previous teams was Bernie White - someone who would never be considered a risk - if they chose to know him," said Charlie Adrion (C'70), a three year letterman and a member of the Georgetown Athletic Hall of Fame who played from 1967-1970. "Bernie was a gentle soul who loved Georgetown academics (as did many of the white basketballers of the era). He was a proud man and as I recall enjoyed spirited conversations with Coach Magee. Gone now, I remember Bernie as the only player who cared enough about me to gently scold me that I was not taking full advantage of the academic opportunities at Georgetown. He was right - I avoided them."

Though recruited by O'Keefe, White's career at Georgetown came under the coaching tenure of Magee, who didn't recruit him and let him sit on the bench for most of his three seasons. Frustrated by a lack of playing time, White quit the team midway through his senior season and earned his degree in 1969.

"It must have been difficult for him," Adrion said. "He was never a Magee favorite for playing time, but he had great attitude and was solid with the other players suffering that fate."

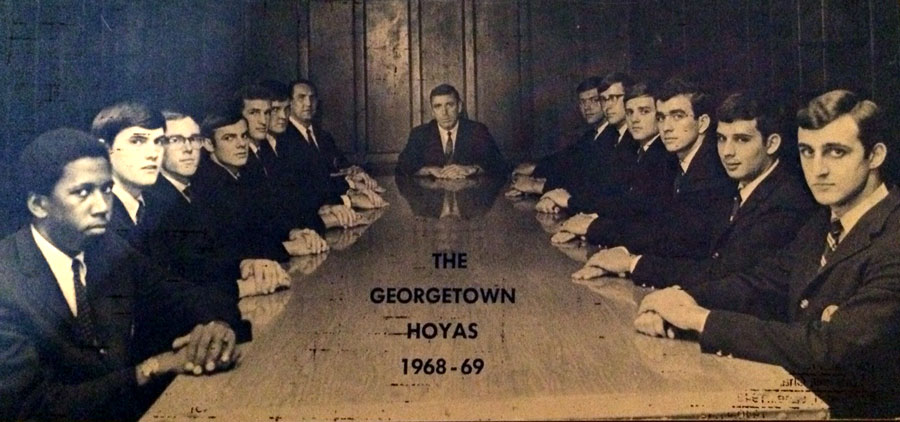

Over his first two seasons, Magee had not signed a single black player to his team, lacking recruiting contacts in the Washington area and focusing instead on Georgetown's usual feeder schools in the Catholic leagues of New York and northern New Jersey.

"For the most part, the disinterest in diversity, and serving a wider community, extended down to the high school environment that I grew up in," said Adrion, who won a state basketball title at Don Bosco Prep in Ramsey, NJ. "The pool of black players in the area Georgetown focused on was not really target-rich, certainly not like the recruitment possibilities closer to home in DC or Baltimore. So how and why did this misguided (at least from a cultural and athletic perspective) focus originate and perpetuate? Partly, for sure, fear of 'the other'. The wall around the Georgetown campus was not only physical, we were an island of white in a black city. Half of Northwest DC could be included in this, AU and GW too."

In 1969, Magee announced the addition of a first-ever black assistant coach at Georgetown: George Leftwich, a former teammate of John Thompson who later starred at Villanova, replacing Bob Reese. Leftwich turned down the offer to remain a high school coach at Carroll.

"Georgetown is the finest and the student body deserves good teams," said Reese upon leaving the team. "The situation there is a shame."

Three events at the conclusion of the 1960's would do to Georgetown what it institutionally could not do on its own - initiate change.

By 1968, the life of a Georgetown student was in sharp contrast to the life of his city. In a region that endured widespread poverty and a 30 percent unemployment rate for black citizens, Georgetown still stayed remarkably focused on itself. The April 4, 1968 issue of the HOYA covered the upcoming U.S. presidential elections, noted a five game schedule for the school's polo team, and published a page long essay entitled, "Can Parochialism At G.U. Be Cured?"

"No one can ask for a revolution here and now; but could we not achieve a shift in emphasis, a change in tone?" asked Rev. Raymond Schroth S.J. "Aren't there a number of moves this community could make that would identify it more clearly with the needs of society, particularly the poor?

"To so many it is a city on a hill. It is a Flemish tower, John Carroll splattered with red paint or with a girl in his lap. The Chimes, polo, football with booze and fist fights after the Fordham game, the "Dip's Ball," a living link with the days in which Jesuits owned estates, bright sun on the tennis courts, Randall Reading Room at midnight before a Chemistry test, or Friday night at the '89. Each, in its own way, a beautiful thing without which life would be poorer indeed. But what central image does the university want to project?"

He concluded: "On my corridor bulletin board this evening, March 29, there are two signs side by side. One asks, 'Have you ever gone hungry?' and urges support for Martin Luther King's Poor People's Campaign; the other says, 'Drink Your Way Around the World'...Will the real Georgetown please stand up?"

That same day, Dr. King was shot to death in Memphis, beginning five days of riots which shook the Nation's Capital, killed 28, and burned 900 businesses in the downtown area. If Georgetown was physically spared from the riots, it opened eyes at the highest levels of the University that it could no longer be a passive observer in its city, and that work had to be done.

A year later, the student body would change as the first women enrolled in the College. The headline in The HOYA, "Tradition Crumbles; College Adds Girls" was about more than than a change in tradition. By diversifying the admissions pool, Georgetown found out that women applied at a higher rate than the men, many with better grades. It was also pointed out that in an era where Georgetown was struggling financially, it expanded enrollment and brought in a new source of tuition revenue.

As women arrived on the Hilltop, the admissions office was also at work with the University in committing to multicultural student admissions, which started with the Washington area itself. Under the leadership of incoming university president Robert Henle S.J., undergraduate admissions director Joseph Chalmers, and assistant director Charles Deacon (C'64, G'69), the Community Scholars Program (CSP) was created to support admissions and financial aid for minority applicants, particularly those in the District of Columbia to whom a Georgetown education was considered out of reach. By seeking to admit local students at no less than the criteria used to admit Georgetown's existing legacy candidates, the CSP would admit students without raising charges of unfair or disproportionate standards.

It was not well received in some quarters.

"A lot of the older alumni accused me of turning this place into a black institution," Rev. Henle said in 1975. "With the miserable number of blacks we were able to admit over the years, they still said 'You're crazy, you're going out and taking in blacks who are inadequate.'"

"I answered every dumb letter I got," Henle said. "In many cases they thought something was happening here that wasn't happening."

And then there was basketball. In 1970, Georgetown earned its first post-season bid in 17 years.

"It was the birth of Georgetown basketball," said Mark Edwards (B'73), who was a freshmen during that season and joined the varsity in 1970-71. Edwards was Magee's first African-American recruit, a 6-5 forward at DeMatha HS in an era where Georgetown freely admitted they didn't recruit Dematha players.

"To accept a boy that can't do the work hurts everybody. It hurts the boy, the team, and the school. That's the reason why we don't recruit the Washington schools like DeMatha and Mackin," said assistant coach Bob Reese a year prior to Edwards' arrival.

Edwards wasn't one to back down. He was more Georgetown than a lot of Georgetown people.

Mark Edwards grew up east of Wisconsin Avenue in Georgetown when it was still a predominately black community. He attended Holy Trinity School on 36th Street across from the University, in part because the Catholic parish east of Wisconsin Avenue (Epiphany) didn't build a school. And despite scholarship offers from Texas, Miami, and San Francisco, he chose to attend Georgetown in the fall of 1969.

If he had gone to Texas, Edwards said, he would have been the first black athlete ever admitted to that school. His mother told him to avoid Miami ("a party school", he recalled) and San Francisco wasn't her favorite, either. "She said there were too many hippies there," he said. Georgetown, he said "was the perfect fit for me."

The 1969-70 team, the last recruits of Tom O'Keefe's years at McDonough, was something special.

A perennial .500 club in Magee's first three seasons, the 1969-70 Hoyas caught the campus' attention. With a mix of youth and returning experience, the Hoyas won 12 of its first 14 games en route to its best record in 23 years. Its post-season hopes appeared to have been grounded in a 66-49 loss to Manhattan at Madison Square Garden on Feb. 12, 1970, but when the Hoyas defeated Penn State in the season finale, it earned an invitation to the NIT.

Georgetown's subsequent 83-82 loss to Louisiana State in the first round was no defeat in the eyes of thousands of students and alumni who filled Madison Square Garden for the game, and for thousands more who were treated to a rare nationally televised game on CBS. Georgetown basketball was on the map, and folks wanted it to stay that way.

Following the loss, Magee was already looking forward, telling a reporter "I think John Connors has the potential to be a fine player, Mark Edwards is going to provide us with strength, both are very intelligent players."

"Washington is another area that's starting to make a dent and we're talking to several players. Actually, if you can recruit out of New York and Washington, you don't have to go to too many other places," he said.

"It's starting to take on a new dimension now: kids are starting to look at basketball here."

Edwards joined the varsity in 1970-71, averaging 5.5 points a game in a season that ended acrimoniously, as center John Connors transferred and leading scorer Art White quit the team in a dispute with Magee, who publicly called out White for the team's lackluster 12-14 finish.

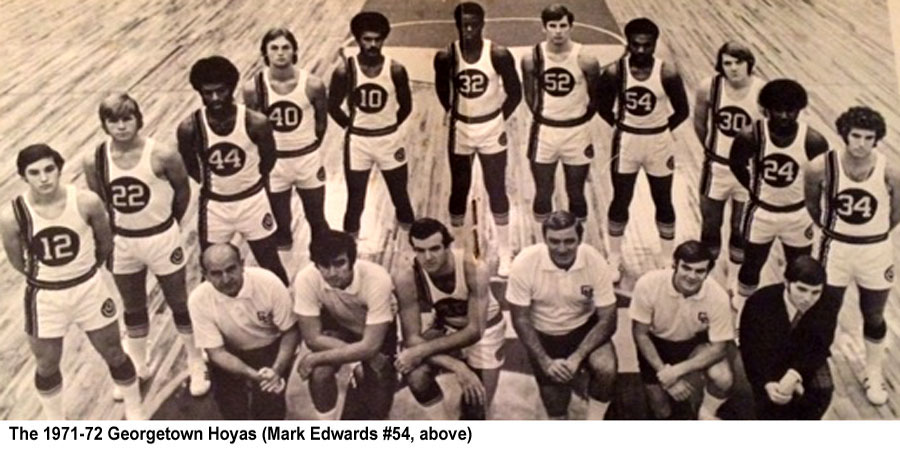

The 1971-72 media guide noted Edwards as an aspiring author and playwright who "enjoys reading philosophical works such as Sartre and Camus." He was also a good recruiter for Georgetown. He welcomed fellow DeMatha grad Don Willis in 1971, as the 6-3 Willis became the first All-Met selection from the Washington area to attend Georgetown since Brian Sheehan in 1957. A pair of sophomores arrived from DeWitt Clinton HS in New York in 6-1 guard Vince Fletcher and 6-6 forward Paul Robinson. As four of the first five African American basketball players at Georgetown, they also maintained a standard that future players were expected to follow--all five earned their degrees.

Edwards assumed a leadership role on the ill-fated 1971-72 team, averaging 10.5 points a game. Realizing that basketball could earn money with so-called "guarantee" games, Georgetown athletic director Col. Robert Sigholtz sent Magee and the Hoyas to a series of distant road trips against top opponents, with predictable results. Games at Marquette, Wisconsin, LSU, Texas, San Francisco and the University of the Pacific rung up nearly 11,000 miles of air and bus travel, with six crushing losses by an average of 24 points per game. Magee resigned under fire on Feb. 8, 1972; Sigholtz was gone a week later. The team lost eight of its final nine to end the season at 3-23.

With the opening, a number of candidates emerged to succeed Magee, among them DeMatha coach Morgan Wooten and former St. Joseph's coach Jack Ramsay, but Charles Deacon, a Washington native and the new director of admissions, had someone else in mind. He suggested it first to Rev. Henle and then to the committee: St. Anthony's coach John Thompson, the same Thompson turned down by the College 12 years earlier.

In Curran's book, Deacon remarked that "most of us were very aware of of what an impact a successful basketball team, with a black coach, would have on the image of Georgetown...both locally and nationally."

The search committee voted for Thompson, though, as Edwards noted, Fr. Henle had something to say about it, too.

"Fr Henle liked to say he always had 51 percent of any argument he was in," Edwards said.

He added: "Henle did this, Deacon did this," and "this" was more than basketball, but the beginning of an era that sent Georgetown University ascendant. With the enthusiastic support of Henle and of his successor, Rev. Timothy S. Healy, S.J., the wheels of the University - admissions, scholarship, reputation, and philanthropy - began to turn, with a basketball team leading the parade. A conference, the Big East, followed. Within three years, a trip to the Final Four. Just ten years since his hiring at the age of 30, John Thompson had helped take Georgetown University, not just basketball, to the national stage - a team that represented confidence, hard work and a sense of purpose, but not at the loss of its academic or civic responsibilities.

Georgetown was not only associated as a Top 25 basketball program, but would soon take residence as one of US News' top 25 universities. The synergy was no accident.

But this was no longer the Georgetown University of 1960 or even 1970. The response to John Thompson on that day in New Orleans was a recognition of a new and different Georgetown, one whose mission statement would later be revisited to reflect a outlook that reached horizons beyond that of its more parochial predecessors. While there was (and remains) more work to be done, the call to action was clear. "The University was founded on the principle that serious and sustained discourse among people of different faiths, cultures, and beliefs promotes intellectual, ethical and spiritual understanding," it reads in part. "We embody this principle in the diversity of our students, faculty and staff, our commitment to justice and the common good, our intellectual openness and our international character."

And basketball helped Georgetown across the line.