1972

December 3, 2021

On December 3, 1971, the Georgetown men's basketball team boarded a bus outside McDonough Gymnasium to travel to its season opener. Amidst dropping temperatures in the Nation's Capital, the longest, coldest season in Hoya basketball was about to begin.

The structure of men's basketball at Georgetown University still runs along the fault line created from the 1971-72 season--not merely in its record, but in the reconstruction of the program which followed. The phrase "Hoya Paranoia" may have been coined in 1980 to suggest a basketball program which operated in stealth, but the approach was in stark contrast to a very public, very bitter season which preceded it eight years earlier.

The 1971-72 team was a low point for an inexperienced team and a fractious administration which surrounded it. A 3-23 record was only part of the story. The players were set up for failure--sent on the road for 16 of 26 games totalling nearly 12,000 miles of travel, not for the promise of competitive glory but to settle a grudge: an athletic director who wanted to run off the basketball coach. Sixteen road games, sixteen losses. Twelve student-athletes were caught in the crossfire, or as one said at the time, they were just being used.

It was the season that fundamentally changed the role of basketball at Georgetown.

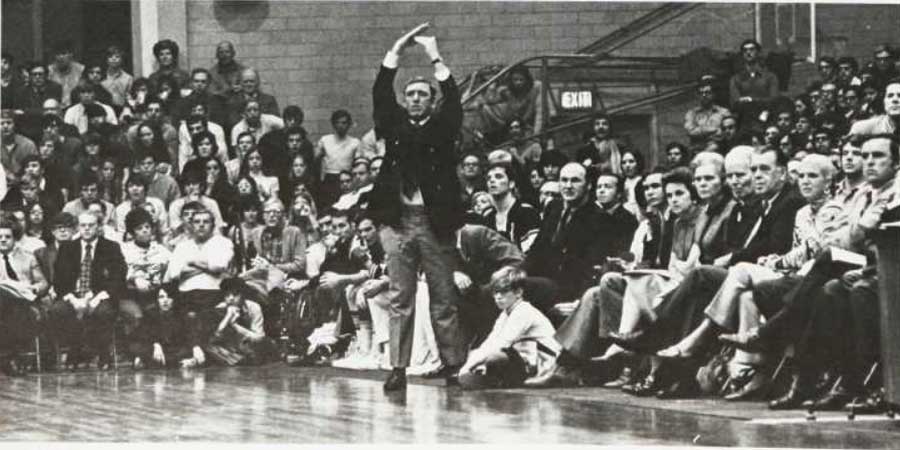

An account of this era is limited given the passage of time, but I placed a call to a man who witnessed it first-hand: Jack Magee, the Georgetown men's basketball coach from 1966 to 1972. With a sharp mind calling back memories of games as if they were played last week, the 86 year old Magee provided a valuable, first-person perspective on a cast of characters which sent Hoya basketball to cross its own version of the Rubicon.

Jack Magee grew up in New York and earned a scholarship to Boston College. The leading scorer on BC's first NCAA tournament team in 1958 under head coach Don Martin, Magee graduated as its team captain in 1959 and returned to the Heights in 1961 following military service.

"I went to Don Martin and told him I wanted to get into the business," Magee said. Martin, a 1942 Georgetown grad, brought him onto his staff as a volunteer assistant, but unexpectedly retired from coaching a year later. After a year with freshman basketball coach Frank Power serving as the interim coach, BC hired Boston Celtics legend Bob Cousy to lead the team. Magee was retained as the lead assistant, working the off-seasons as a teacher for special needs children at Boston's Catholic Memorial High School.

In 1966, upon Cousy's recommendation, Magee applied for the vacant coaching position at Georgetown. "I interviewed for the job in a Washington law office downtown, because they didn't want to tell the media. One of the interview questions was from a priest, who asked me, 'What do you do with players with bad hands?' Well, first you don't recruit them!", he laughed.

Magee was hired in the spring of 1966 and became Georgetown's first full time basketball coach since 1949, armed with a $12,000 a year contract and an additional stipend to serve as GU's part-time golf coach, which he described as "driving the van and handing out the golf balls." His arrival was announced in the city's three daily newspapers and in the Congressional Record, where Rep. Thomas O'Neill went to the well of the House of Representatives to offer this statement: "Mr. Speaker, Georgetown University has announced the appointment of Jack Magee as varsity basketball coach. Jack Magee has for the last few years, been the top assistant to Bob Cousy at Boston College. Jack is an outstanding young man who takes great ability and dedication to Georgetown...I take this time to congratulate [him] and to compliment Georgetown on selecting this fine young man, who, I am certain, will be a credit to this great university. As a fellow graduate of Boston College, I welcome Jack to the Capital of the Nation."

As a head coach, "I was very inexperienced," Magee said. "It was not bad, however. The first three years we were .500, that's what it was the last 15 years before then. I was blessed with an athletic director who was absolutely wonderful, Jack Hagerty. He retired in 1969, and they hired Colonel Sigholtz. Not only was he not skilled, he thought he was completely skilled, which immediately made it worse."

Magee's foe over the next three seasons was Lt. Col. Robert Sigholtz, a a 48 year old veteran of three wars who joined the University two years earlier as its ROTC director. A year later, he was reassigned as Hagerty's heir apparent, and became athletic director in the fall of 1969. With what the Washington Post graciously called "a strong personality", Sigholtz was a lightning rod for student criticism, so much so that seven of Georgetown's 12 team captains petitioned the University to have Sigholtz fired before he even became director.

The appointment of Sigholtz was part of a widespread changing of the guard in the late 1960's. Athletics and a number of disparate departments including Residence Life, Campus Ministry, Career Placement, and Student Health were placed under a single organization, University Services, led by the first woman at GU to serve as a vice president, Patricia Rueckel, 38, a psychology professor and the former Dean of Women from 1961 to 1968.

The appointment of Sigholtz was part of a widespread changing of the guard in the late 1960's. Athletics and a number of disparate departments including Residence Life, Campus Ministry, Career Placement, and Student Health were placed under a single organization, University Services, led by the first woman at GU to serve as a vice president, Patricia Rueckel, 38, a psychology professor and the former Dean of Women from 1961 to 1968. As the newly titled Dean of Students, Rueckel was a seen as a breath of fresh air. In 1969, she set up a table on Healy Lawn along the lines of the "Peanuts" comic strip to meet students, sitting behind a table with the sign "The Doctor Is In". The photo was widely distributed, putting Rueckel on the pages of the New York Times and the International Herald Tribune. She was even a guest on the television game show "To Tell The Truth", where she won $500 when a celebrity panel failed to select her among two others also claiming to be the dean.

In the new organizational structure, Magee reported to Rueckel, not Sigholtz. By her own admission, Rueckel chose not to take an active interest in managing athletics amidst her other varied responsibilities.

Athletics comprised 42 percent of the University Services budget. To provide further administrative support, Rueckel enlisted an assistant vice president: David Trivett, a 28 year old social scientist from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Trivett, however, professed little interest in competitive sports. Thus began a series of pointed fingers across the administrative landscape: Sigholtz wouldn't work with Magee because he was not a direct report. Rueckel wouldn't work with Magee unless it was through Trivett.

"It was like talking to a wall," Magee recalled. "The three of them had no clue."

Magee ended the 1968-69 season 12-12, and was an even 35-35 after three seasons. In his fourth season, the Hoyas rallied to an 18-6 record, with eight come from behind wins. As a result, Georgetown was selected for the National Invitation Tournament (NIT), its first post-season appearance in 17 years. Magee worked the phones to get Georgetown the prime opponent in the tournament: the LSU Tigers, led by the nation's leading scorer, Pete Maravich.

"I talked our way into getting LSU," Magee said. "Ben Carnevale was running the NIT. I went to him and said, Ben, if we play LSU, I promise we will not hold the ball," addressing a concern by network officials that an undermanned opponent would simply hold the ball the entire game and rarely shoot, making the game a ratings dud. CBS, unaccustomed to covering basketball, enlisted NFL announcers Pat Summerall and Jack Whitaker for the unusual Sunday afternoon broadcast.

"I talked our way into getting LSU," Magee said. "Ben Carnevale was running the NIT. I went to him and said, Ben, if we play LSU, I promise we will not hold the ball," addressing a concern by network officials that an undermanned opponent would simply hold the ball the entire game and rarely shoot, making the game a ratings dud. CBS, unaccustomed to covering basketball, enlisted NFL announcers Pat Summerall and Jack Whitaker for the unusual Sunday afternoon broadcast.Georgetown got the first round matchup with LSU for national television, its first such game in school history. Citing a phone call from Howard Garfinkel and a coach that relayed to him a defense used against high scoring Marquette guard Dean Meminger, Magee recalled his strategy against Maravich: "a triangle in the back with a guard at the top in front of the center, we then double-teamed Maravich most of the time as a result."

"It wasn't all [Georgetown guard] Mike Laska but he did a great job."

Maravich was held to 20 points, down from his season average of 44.5. LSU escaped with an 83-82 win before 16,021 at Madison Square Garden, the largest crowd that had ever seen a Georgetown game to date.

Amidst the notoriety received from the NIT, Magee was approaching the end of his contract and still had not received an extension.

Fordham University reached out with an offer, but Magee, who grew up in New York and was not looking to relocate his family there, declined. "I talked to Peter Carlesimo, their athletic director. Get yourself a young coach." Carlesimo hired Richard (Digger) Phelps, a 29 year old assistant at Penn. With considerable talent inherited from former coach Ed Conlin, Phelps led the Rams to a 26-3 record in his first season, and was promptly hired away by Notre Dame, coaching there for the next 20 years.

Magee was then contacted by Holy Cross, where coach Jack Donohue was reportedly looking elsewhere. "They wanted me at Holy Cross, it would have been good there," he said, but when Phelps went to Fordham, Donohue opted to stay in Worcester.

Jack Magee stayed in Washington.

"I like it here, I can see a great deal of potential here, I think we've made tremendous strides so far," Magee said in a 1970 newspaper interview. "Despite some of the things that have been said about us in the past, I think now people are starting to eat some of the words they threw out. It makes me kind of happy as it does the kids. We were told on a number of occasions that we have no ball players, oh many things, and I think we as a team, coach included, have shown quite a few people that maybe we were right and they were wrong."

"[As to the athletic director], we do have a communication problem. Sometimes it's a lack of understanding for the problems of a basketball team, of a basketball coach. I am not totally happy along these lines; I think there's a great deal of room for improvement, and I'm sure that the same thing is thought of on the other end."

Magee proposed a three year contract and offered to take a pay cut. He lobbied for more support: an academic counselor for the players, a refurbished locker room, better office space for the coaches. He got none of it, but received a two year extension.

Expectations were raised for the 1970-1971 season but the team reverted to form, finishing 12-14. Complaints about Magee's coaching and recruiting, held in abeyance during the 1969-1970 season, nonetheless reemerged, and not just among fans. It was reported that Col. Sigholtz had approached alumni to help him buy out the last year of Magee's contract, which they declined, and allegedly offered assistant coach Ed Hockenbury the head coach's job, were Magee to be let go early. Hockenbury said no, and he resigned.

Even the simple question, who made the final decisions on basketball, had no simple answer.

Robert Sigholtz was the athletic director, but without budgetary authority. Patricia Rueckel owned the budget, but not the allocation. The Athletic Advisory Board, created in 1966 following the end of Jesuit control over the athletic department, was a committee of faculty and student representatives that approved general athletic policy, budget allocation, and schedules. Its recommendations could be accepted, rejected, or even ignored. However, neither Magee nor Rueckel had a seat on the board.

Outside the meetings, there was often no public consensus. One faculty member on the board was quoted as saying "I think it's a good policy not to field a nationally prominent team." Another professor offered this assessment of the athletics landscape: "We don't know what we really want."

With one year remaining in his contract, Jack Magee approached the board in the spring of 1971 asking for clarity on whether his contract would be renewed, or if he needed to start looking elsewhere. He never received a response.

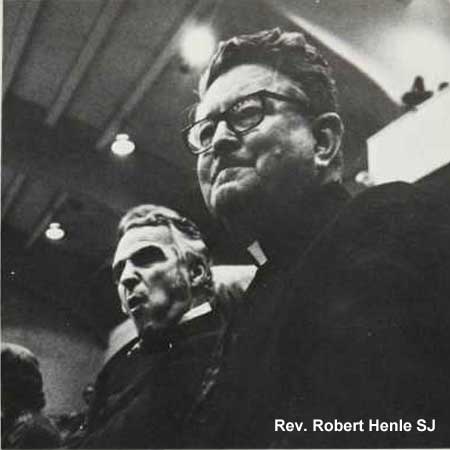

At the top of the organization chart was Rev. Henle, whose closest view of athletics was an occasional seat at a basketball game. In a 1971 interview, Henle remarked that "I know Colonel Sigholtz would like to speak directly with me, but I've got so many people reporting to me and really I don't see how that would be an advantage to the athletic people. Frankly, I don't really know anything about athletics."

At the top of the organization chart was Rev. Henle, whose closest view of athletics was an occasional seat at a basketball game. In a 1971 interview, Henle remarked that "I know Colonel Sigholtz would like to speak directly with me, but I've got so many people reporting to me and really I don't see how that would be an advantage to the athletic people. Frankly, I don't really know anything about athletics.""Yes, I can see how there's a difficulty," he added, "but I don't think that this ought to discourage them from getting together. If they really will make proposals and work out long range plans, they're bound to get up here. But I must go through channels. I can't ignore all the intermediate people."

The Hoyas lost four starters and five seniors overall from the 1970-71 season. Its 6-9 sophomore center, John Connors, was suspended late in the season and transferred to Manhattan. Art White, the team's most promising scorer as a junior, quit school. Georgetown entered the new season with one returning starter (senior Mike Laughna, at 17.7 ppg), four reserves who combined for just eight points a game between them the previous season, and seven newcomers.

The inexperience of the team was compounded by a schedule that was suicidal. Sigholtz took over scheduling for the 1971-72 campaign and dropped six regional opponents that Magee had gone 5-1 against in 1970-71, for an expansive six game road trip from Dec. 27 through Jan. 13: Marquette, Wisconsin, LSU, Texas, San Francisco, and Pacific. Including two in-season tournament opponents, the teams that were not renewed from the previous schedule finished a combined 97-100 that season (.492), and were replaced by teams that were a combined 136-72 (.653).

The Hoyas would be sent on the road for ten of its first 12 games. The Georgetown basketball media guide began with this blunt assessment: "A frank evaluation of 1971-72's basketball prospects would have to be a questionable one."

And so it was.

Georgetown began the season with a 103-93 loss at Boston University, and were clocked by St. John's in the McDonough opener, 107-67, the worst home loss in school history, then or now. The Hoyas would finish 210th of 219 Division I schools in points allowed, and defense was a story all season. The first win followed in a 82-66 win over Loyola, but hopes were fleeting. A week later, #5-ranked Maryland walloped the Hoyas, 79-46, its largest win in the series and a 50 point swing from GU's 96-79 win over the Terrapins a year earlier.

Following exams and the Christmas holiday, the gauntlet began: a 88-44 loss to #2-ranked Marquette, a 82-62 loss to Wisconsin the next evening. Returning to campus for three days, the Hoyas were back on the road after New Year's: a 92-71 point loss at LSU, a 78-70 loss at Texas. Three days later, Georgetown was now in California, falling 100-76 to San Francisco and 105-73 to Pacific. The team returned with a 1-9 record.

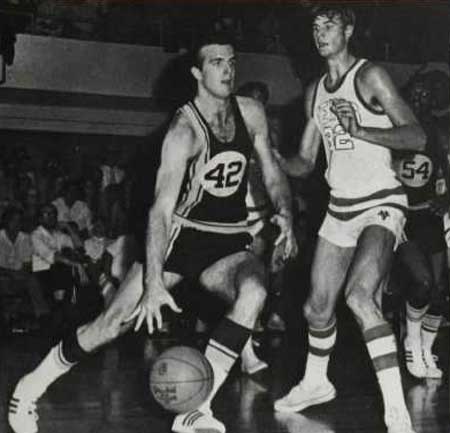

An eighth consecutive road game dispatched the Hoyas in mid-January to Randolph-Macon College, a Division III team Georgetown had defeated by 17 points the season before. Georgetown shot 56 percent from the floor and led by 10 midway in the second half, but the Yellow Jackets won the game at the foul line, a 73-72 upset. Laughna had 21 points and 10 rebounds, breaking the school's career rebounding mark, but the big story in the Post the next morning was a six column headline at the top of the page, titled "We're Being Used, Georgetown Star Feels"

An eighth consecutive road game dispatched the Hoyas in mid-January to Randolph-Macon College, a Division III team Georgetown had defeated by 17 points the season before. Georgetown shot 56 percent from the floor and led by 10 midway in the second half, but the Yellow Jackets won the game at the foul line, a 73-72 upset. Laughna had 21 points and 10 rebounds, breaking the school's career rebounding mark, but the big story in the Post the next morning was a six column headline at the top of the page, titled "We're Being Used, Georgetown Star Feels"A mid-season vent by Mike Laughna to Kenneth Turan about athletics at Georgetown filled the upper front page of the sports section.

"An athlete at Georgetown has to feel a bit screwed," Laughna said. "I think we're being used--the administration's trying to get so much out of us and not putting anything in."

No one was spared--overzealous fans, hostile faculty, indifferent administrators. Such thoughts are often left in a locker room, but the Post gave Laughna's grievances a very public airing.

"There's a separation between scholastics and athletics; one never realizes the other exists," Laughna continued. "Some professors are understanding, and thank God for those people. Others just close the door on you. When the head of your department does it, you get rather depressed."

Laughna never called out coaches or teammates, but took aim at the administration. "These trips may be lucrative for the school -- I heard we got $10,000 for being in the Milwaukee Classic-- but to get it they had to go through the players' morale. They're taking advantage of us, pitting us against incredible teams where the odds in our favor are not really there."

"It's been like the longest season in the world, incredible, that's all there is to it. It's been brutal."

Alumni urged the athletic department to address the issue. Sigholtz hastily announced a news conference where he handed out copies of what he called a "basketball fact sheet" to refute the claims of mismanagement. It was met with skepticism by some and outright disbelief by others.

"Sigholtz said that the release was compiled by him and that head basketball coach Jack Magee had nothing to do with the compilation of the release," wrote The HOYA. "Sigholtz insisted that Magee was not consulted as to the contents. When asked why, Sigholtz replied that 'The report deals with administrative matters and I only consult Magee on technical matters.'"

The fact sheet claimed that Magee arranged the schedule (refuted by those familiar with the situation), that Magee had not used his full recruiting budget, and confirmed that Sigholtz, not Magee, scheduled the game at Maryland during exam week.

In our recent conversation, Magee took an opportunity to clarify the details on the Maryland game. "Lefty [Driesell] called me about a date, we couldn't get together on a date. I asked, do we have to play [this year]? Lefty said, OK, let's skip it. Then Sigholtz said, we can't do that, [so] he took over scheduling."

While the press conference was spurred by the Washington Post article, Sigholtz declined comment on any of issues raised in the article, leading many to question why he held the press conference in the first place, if not simply to embarrass Magee and deflect responsibility for Laughna's comments amidst the losing season to date.

"As a reply to Laughna's remarks, the report fails," wrote The HOYA. "As an insight into the inner problems of the Athletic Department, it readily succeeds."

The losing streak reached nine games with a 98-72 loss at Seton Hall before an overtime win over William & Mary at McDonough Gymnasium brought a second win on the season. Nonetheless, the players were drained, as was the coach.

"I didn't recognize how difficult it was," Magee recalled. "In retrospect, after all of it was over, I did a bad job on those road trips because I was down and didn't realize it. I threw the towel in. I had nobody [at Georgetown] to go to."

Entering February, the Hoyas were 2-12, and the question of Magee's departure seemed a foregone conclusion. The Athletic Advisory Board met with Magee on February 7. Following a five hour meeting, the board failed to take a vote to retain Magee or dismiss him, despite his contract expiring in four weeks. Magee had enough, and sent a two sentence letter of resignation to Rueckel, effective at season's end.

"I was disgusted with the whole process," Magee said in retrospect.

A week later, the board turned its scrutiny to Sigholtz, but surprisingly voted 6-1 to retain him. Rev. Henle, perhaps seeing the dysfunction Sigholtz would bring upon a new head coach, overruled the board and asked for Sigholtz to resign.

Following Sigholtz's departure, Henle named Frank Rienzo, 39, as the new athletic director. Though he had no formal experience as an administrator, the promotion of Rienzo was praised for providing a new beginning for a department which had been soured by three years of needless crossfire.

At this point, the Hoyas were still playing out the season, with a record of 2-19. A 109-97 win over Hofstra was attended by a season's low of just 561 at McDonough. The schedule ended with three road games in its last four, all losses. On March 4, 1972, a 79-68 loss at Boston College, ended the season with a record of 3-23, 0-16 on the road.

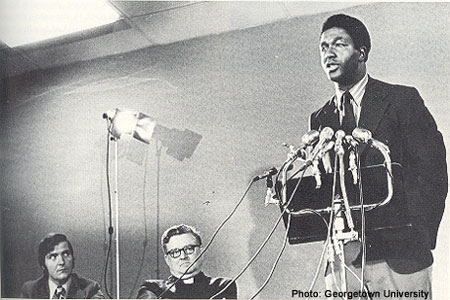

The coaching search was already underway by the close of the season. Over 50 names were in consideration, with three at the top: 30 year old St. Anthony's High School coach John Thompson, 41 year old DeMatha Catholic High School coach Morgan Wootten, and 34 year old Maryland assistant coach George Raveling. The Washington Post reported a fourth candidate in consideration: former Notre Dame assistant Gene Sullivan, 40, who had been passed over for the job that went to Digger Phelps the year before.

Four representatives of the seven man committee were backing Thompson, mindful of his reputation in Washington, D.C. and the need for Georgetown to build bridges with the community at large. Two alumni representatives in the group pushed for Wootten as a more seasoned coach with a pipeline of potential players from DeMatha. When Wootten learned that Thompson was a candidate, he declined to be interviewed unless he was the first choice of the committee, and when that proved not to be the case, he then declared he had never applied in the fist place.

Thompson expressed concern for what he was getting into at Georgetown. He talked to Dean Smith at North Carolina, Dave Gavitt at Providence, and Red Auerbach with the Boston Celtics, each of which offered encouragement. And having known Jack Magee since his playing days at Providence, Thompson asked him whether he should remain in consideration.

Thompson expressed concern for what he was getting into at Georgetown. He talked to Dean Smith at North Carolina, Dave Gavitt at Providence, and Red Auerbach with the Boston Celtics, each of which offered encouragement. And having known Jack Magee since his playing days at Providence, Thompson asked him whether he should remain in consideration."I got a call from John asking, What do you think I should do?", Magee said, noting that he had actually tried to hire Thompson as an assistant coach three years earlier. "You've got to report to the president, I told him. You can't stop in-between."

The search committee recommended Thompson as the new head coach. Surprisingly, or perhaps not so, the Athletic Advisory Board failed to take any action on the recommendation at its March 9 meeting. Henle bypassed the board and made the offer himself.

"[Thompson] came through absolutely superior to anyone else," Rev. Henle told Leonard Shapiro in the 1991 book Big Man on Campus. "I offered him the job and he said he wanted to add a new staff member, an academic advisor to ride herd on the players, and I said, you've got it. He said, I want to be an educator, I want them all to get a Georgetown degree, and I told him that's exactly what I wanted, too. I told him I wanted a team that would get a national reputation. I asked him how many scholarships he needed, and whatever it was I gave it to him. Hiring John Thompson was one of the best things I ever did there."

In his introductory press conference, Thompson said that his ambition was to lead the Hoyas to the post-season, but noted that "a lot of work has to be put into the program to reach that level." Years later, Thompson told the story that Henle said he would just be happy if the Hoyas could just get to the NIT every few years or so. Thompson's first contract was a four year deal at $20,000 a season.

By the summer of 1972, Thompson got what he needed to succeed -- latitude in recruiting, support in admissions, complete control over scheduling, and a direct line of authority to the President's office. The Athletic Advisory Board was out of the basketball business, and eventually faded out of view over the next decade.

"The Administration only began to take action after the conflict got out of hand, which only goes to prove their lack of ability in handling athletics," wrote the 1972 school yearbook. "It is redundant to say that things must change, but unfortunately true to say that things cannot get much worse."

While John Thompson went to work rebuilding the basketball team, Frank Rienzo faced a different challenge: rebuilding an athletic department that had no direction from above and serious questions to answer as to its future.

Over his three years at athletic director, Robert Sigholtz had initiated a number of efforts to raise funds for athletics, including the formation of an annual giving organization which raised $12,000 in its first year. "I believe athletics can do a lot for a university's giving program," Sigholtz said. "Athletics is a cohesive factor in bringing the University together."

But in the world of non-profit accounting at Georgetown, revenues failed to flow back to the department. In the 1972-73 fiscal year, men's basketball earned $25,408 from 13 home games, but none of it went to the team itself. Because athletics was only a cost center, revenues flowed to the University Services budget while expenses were allocated to the cost center. This was cited by Laughna in his 1972 Washington Post feature, claiming basketball funds were "diluted everywhere else. We're helping the soccer team, everyone...I think we should be given preference."

In 1972, Georgetown allotted just over $130,000 of operating expenses for its 12 men's sports, with three teams (basketball, track, and football) consuming 82 percent of the total. Other sports received as little as $1,000 a year for operating expenses. In some cases, minor sports lacked the funds for event registration fees or to pay officials to referee the games.

Further complicating matters: a new law known as the Education Amendments of 1972, or more specifically, Title IX. The College had gone coeducational in 1969 and was approaching a 50 percent female population. The 1972-73 budget allocated just $3,400 combined to six women's sports, none of whom had scholarships or full time coaches. Title IX was still evolving but the direction was clear: colleges would have to support women's sports-- much, much more than they were doing.

But where would the money come from, at a University planning to reduce costs across the board over the next three years? For Rienzo to fight for the department and his new basketball coach, he needed an edge in the fight, and created what became known as the Georgetown Philosophy of Athletics - a strategy that would define the Georgetown athletics posture to this day.

"As a university with roots in the Jesuit tradition of education, Georgetown commits itself to the development of the entire person," it began. "This requires that Georgetown recognize both the physical and intellectual needs of its students...a sound athletic program at Georgetown must operate effectively on four levels: the intercollegiate, the intramural, the instructional and the purely recreational... successful implementation of the athletic program on all four levels is contingent on an explicit University commitment, visible support and provision of facilities which reflect the philosophy that athletics are indeed part of the educational program..."

The Philosophy was more than an academic exercise. Rienzo's gambit was simple: if Georgetown committed to this philosophy, it would have to add, not subtract, from the budget to meet its larger educational obligations.

Per Henle's directive, copies of the document were circulated among University leadership in the summer of 1972 for review and comment. But as befits a bureaucracy, no one actually returned any comments, and as such, Henle approved it outright at the end of the fall semester.

The Philosophy of Athletics was the preamble for a new view of athletics at Georgetown, including the decision to place intercollegiate programs in tiers for annual funding and long-term support. A group of teams known as national sports would be those programs to which the University would commit to providing full scholarships, full funding, and full-time coaching support, with the expectation to compete at the highest levels of the NCAA--a bold premise given that Georgetown had never consistently competed at that level. Regional sports would compete at a more modest level amongst other programs centered in the Northeast, without significant scholarship support. A third group of lesser funded teams, known as local sports, would compete in and around the Washington D.C. area, where championships were seen as "an extraordinary achievement, but not necessarily a program goal."

The national sports were set at the start: 1) basketball and 2) track and field. Basketball would provide visibility, fan interest, the possibility of post-season competition, and outreach in the Washington DC community. Having just hired John Thompson, to do any less would have counterproductive, to say the least. Track had competed at a high level for Georgetown over the prior 30 years, particularly in cross country and indoor track. While track had no event or training facilities at Georgetown, Rienzo (who also served as track coach) wasn't going to downgrade the sport given its present status in the department. Over time, teams in women's basketball and women's track would join this tier alongside their male counterparts.

Football, the second largest sport by revenue, had only recently returned as a varsity sport after it was dropped in 1951. But without funds to invest in scholarships and suitable gameday facilities, institutional expectations were set that football would never compete as anything more than a regional, non-scholarship effort. This sentiment was echoed forty years later by University President Jack DeGioia, who commented in 2012 that "I am not supportive of moving to a scholarship program. I don't believe that fits the ethos and the culture of Georgetown." One of just two Division I schools remaining in the Northeast that compete for the FCS championship without scholarship support, Georgetown has posted just one winning season in football since 2001.

Also left out of the top tier: baseball. Despite being a full scholarship program, baseball had never qualified for the post-season since the NCAA instituted the College World Series in 1947. Eastern baseball had long since yielded primacy to the south and west for major league talent and Georgetown earned no revenue from its games. Rienzo would later reallocate baseball's 12 scholarships to support women's athletics. Since joining the Big East, the baseball team has not had a winning season since 1986, and lost its on-campus field in 1999 to University construction projects.

Fifty years later, the tiering, formally or informally, still exists. Lacrosse and soccer joined the national level in succeeding years, with considerable success that followed for both. The development of the Big East conference effectively upgraded all the local sports to the regional tier, but the ceiling on scholarships still remains a hurdle that most Georgetown teams struggle with to compete. Of the 18 sports teams below the national tier at Georgetown, none are likely to be elevated to this level, and just as importantly, no one at the national tier is at risk of being relegated.

As far as men's basketball is concerned, it's still king of the Hilltop. Basketball consumes 57 percent of operating expenses for the department, up from 42 percent in 1972. Add in scholarships, recruiting, travel, overhead, and coaching salaries, and men's basketball is not only the most visible sport at Georgetown, but one of the 20 largest college basketball programs by budget in the nation. Public data filed with the U.S. Department of Education reports Georgetown spent $13.8 million on men's basketball in 2020-21. As such, it is the only sports team whose coach answers directly to the University president.

When Georgetown fired John Thompson III in 2017, it was obligated to pay more than $7 million from the remaining years of his contract, per public records.

Not so in 1972.

"I left with two weeks severance," Magee said.

"I had a family of two young kids, but how do I look for a job in two weeks?" he asked. Recalling the kind words once shown by his former congressman, the coach paid a visit to his office. "So I went to see Tip O' Neill and asked for a job." Jack Magee began a 25 year career in lobbying for the Department of Transportation and later served as chairman of the Massachusetts State Racing Commission.

"John [Thompson] did 99 percent of the things right," Magee said. "I talked to him several times. He did a great job. He took those kids and not only protected them, he disciplined the team and kept them away from the press."

When asked what he took from his coaching career into lobbying, Magee recalled his advice to Thompson: "Always talk to the head boss."

In the years following Georgetown, Robert Sigholtz became the facility manager of RFK Stadium and the D.C. Armory, serving in that capacity for 11 years. He later became a consultant to the National Football League and died in 2004 at the age of 84.

Rev. Robert Henle S.J. served as president at Georgetown University from 1969 to 1976. His firing of Rev. Edmund Ryan, S.J., the school's executive vice president, eroded Henle's support among the Board of Directors, who called for his resignation. Rev. Henle retired to Saint Louis University and died in 2000 at the age of 90.

Mike Laughna, whose public comments about the state of the 1971-72 team brought the issue to the pages of the Washington Post, graduated from the College in 1972 and played professional basketball in Europe before beginning a career in the energy sector. He died in 2012 at the age of 62.

Patricia Rueckel was a vice president at Georgetown until 1977 and later served as executive director of the National Association for Women in Education. She died in 2018 at the age of 88. Her former assistant, David Trivett, left Georgetown after the 1971-72 academic year and died in 1978 at the age of 37.

Frank Rienzo served as Georgetown's athletic director for 23 years from 1972 to 1995, setting in course the strategies that elevated Georgetown University to national athletic prominence. One of the four co-founders of the Big East Conference, Rienzo also provided the leadership to elevate women's athletics at Georgetown and led the campaign to build the Yates Field House, a home for intramural, recreational and instructional athletics first identified in the Philosophy of Athletics. Rienzo died in 2018 at the age of 85.

John Thompson arrived at Georgetown in the spring of 1972 and was a part of its community for the next 48 years, 27 of those as head men's basketball coach. A three time National Coach Of The Year, Thompson took a school with one prior NCAA tournament appearance to 20 appearances over a 23 year period from 1975 to 1997, including three Final Fours and the 1984 national title, the first NCAA championship in school history. A statue of Thompson stands in the University's intercollegiate athletics center, named in his honor. He died in 2020 at the age of 78, shortly before the release of his long-awaited autobiography.

The tectonic shifts of the 1971-72 season are still felt today--not just in basketball, but across the landscape of Georgetown. Without the changes that grew out of that season, it's difficult to imagine where GU would have ever had the organization, the vision, or the institutional will to compete at the level it does today. The strategy of the last half century has allowed Georgetown to attract many of the greatest players and coaches in its storied history without sacrificing academic performance for competitive excellence. The changes also set in the institutional firmament a hierarchy for men's basketball as the school's premier sport, and a tacit ceiling for many others. Coupled with the arrival of Rev. Timothy S. Healy S.J. in 1976, Georgetown's ascendancy into the nation's academic elite walked side by side with the very public rise of its men's basketball program.

Out of the hard times of 1972, a foundation for the future of Georgetown Athletics was built.

"For the most part it was a wonderful time, and a terrible one, too," Magee said. "I like the wonderful."